Introduction on Perception and Management of Risk

Risk is an inseparable element of social life. Every human society, whether traditional or modern, faces uncertainties that threaten its stability and well-being. From natural disasters and health crises to technological hazards and financial instability, risk is embedded in everyday existence. However, the way societies perceive risk and manage it collectively is not merely a matter of objective calculation—it is deeply shaped by social, cultural, political, and economic contexts. Sociology, as a discipline, provides crucial insights into how risk is socially constructed, how individuals and groups respond to it, and how institutions organize strategies for risk management.

This article examines the perception and management of risk in society from a sociological perspective, highlighting the interplay between culture, power, inequality, and modernity in shaping risk responses.

Table of Contents

Risk as a Social Construct

At first glance, risk might seem like a purely scientific or statistical concept. For example, the likelihood of an earthquake or the spread of a disease can be mathematically calculated. Yet sociologists argue that risk cannot be understood only through objective measurement. Instead, risk is socially constructed, meaning that different communities and cultures interpret and prioritize risks differently.

- In traditional societies, risks were often associated with supernatural beliefs or divine punishment. A drought might have been interpreted as the result of moral failings or anger of the gods.

- In modern societies, risks are framed through the lens of science, technology, and expert knowledge, such as climate change projections or epidemiological studies.

Thus, the perception of risk is filtered through cultural meanings, moral frameworks, and trust in institutions.

Ulrich Beck and the “Risk Society”

One of the most influential sociological theories of risk is Ulrich Beck’s concept of the “Risk Society” (1986). Beck argued that modern industrial societies are increasingly preoccupied with the future and with preventing potential dangers created by modernization itself. Unlike earlier societies where risks were natural (floods, famines, epidemics), in the late modern world, risks are manufactured—such as nuclear accidents, pollution, cyber threats, and global warming.

Key ideas from Beck’s theory include:

- Global nature of risks – Risks such as climate change and pandemics do not respect national boundaries.

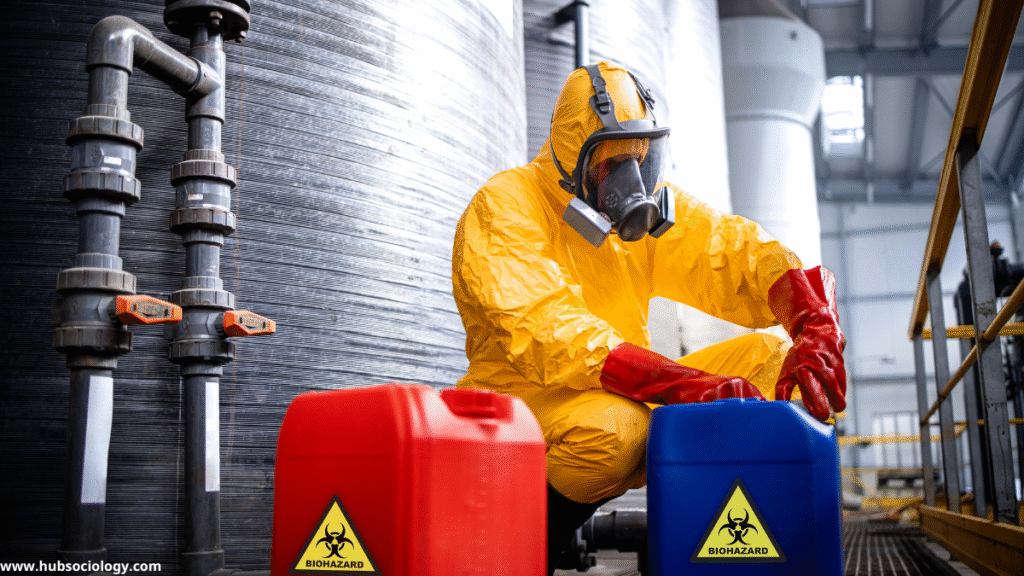

- Invisibility of risks – Many modern risks (radiation, toxic chemicals, viruses) are not directly visible and require expert systems to be recognized.

- Reflexive modernity – Modern society constantly reflects upon and questions its own progress, leading to a heightened sense of uncertainty.

This theory highlights how risk perception is linked with technological advancement, globalization, and institutional trust.

Cultural Theories on Perception and Management of Risk

Mary Douglas and Aaron Wildavsky (1982) provided another influential perspective with their Cultural Theory of Risk. They argued that risk perception is shaped by cultural biases and social organization rather than objective threats. For instance:

- Hierarchical societies (with strong authority structures) perceive risks as manageable through rules and regulations.

- Individualist cultures tend to downplay risks, focusing on personal responsibility and freedom.

- Egalitarian groups emphasize environmental and social risks, stressing collective responsibility.

- Fatalistic communities often view risks as unavoidable and beyond their control.

This theory shows that risk is not merely an external reality but reflects the values, worldviews, and power dynamics of a society.

Media and Risk Amplification

The role of media is central in shaping public perceptions of risk. Sociologists note that risks can be amplified or minimized through news coverage, social media, and cultural narratives.

- Moral panics occur when the media exaggerates certain risks, such as youth delinquency, drug use, or terrorism, creating disproportionate fear.

- Conversely, some risks may be downplayed due to political or economic interests, such as environmental pollution by powerful corporations.

The media does not merely report risks but frames them in ways that shape collective anxieties, influence policymaking, and direct social responses.

Inequality and Risk Distribution

Sociology also emphasizes that risks are not equally distributed. Risk is closely linked to social inequality. Poor and marginalized communities are often more exposed to risks and less capable of managing them.

Examples include:

- Vulnerability of low-income populations to natural disasters due to inadequate housing.

- Disproportionate exposure of workers in hazardous industries to occupational risks.

- Unequal access to healthcare during pandemics, leaving marginalized groups more vulnerable.

The concept of “environmental justice” addresses how risks related to pollution, climate change, and resource exploitation disproportionately affect disadvantaged communities. Thus, managing risk is also a question of social justice.

Institutional Responses to Risk

Societies manage risk through a variety of institutional mechanisms:

- Government Policies and Regulations – Laws related to safety standards, environmental protection, public health, and financial systems aim to reduce risks.

- Scientific Expertise – Experts provide risk assessments, though their authority may be contested by laypeople.

- Insurance and Welfare Systems – These act as buffers, redistributing risk and providing security in uncertain situations.

- Global Cooperation – Issues like climate change, terrorism, and pandemics require international risk management strategies.

However, public trust in these institutions is crucial. Scandals, misinformation, and failures of governance often lead to skepticism about risk management efforts.

Risk and Globalization

In a globalized world, risks have become increasingly interconnected. A financial crisis in one country can spread globally; an outbreak of a virus in one region can turn into a pandemic. Globalization has created what sociologists call “risk interdependence.”

This interconnectedness complicates risk management because local decisions often have global consequences. Moreover, the rise of transnational corporations and international organizations shifts responsibility beyond the control of individual states, raising questions about global governance and accountability.

Community and Everyday Risk Management

While much focus is placed on institutional and global risks, everyday life also involves constant risk negotiation. Individuals and families develop coping strategies based on cultural beliefs and social networks. For example:

- In rural communities, traditional knowledge is used to predict weather risks or manage agricultural uncertainty.

- In urban contexts, families rely on social networks for financial or emotional support during crises.

- Informal community organizations often step in where formal institutions fail, such as neighborhood groups mobilizing after disasters.

These micro-level practices demonstrate the resilience and agency of individuals in managing risks.

Toward a Reflexive and Inclusive Risk Management

Sociology highlights that risk management must go beyond technical solutions to include public participation, cultural sensitivity, and equity considerations. Effective risk governance requires:

- Dialogue between experts and laypeople, acknowledging public concerns.

- Transparent communication to build trust in institutions.

- Policies addressing inequality, ensuring vulnerable groups are protected.

- Reflexivity, where societies critically examine the unintended consequences of modernization and technological advancement.

Conclusion on Perception and Management of Risk

The perception and management of risk in society cannot be understood merely through statistics or technical expertise. Risks are socially constructed, culturally interpreted, and unequally distributed. From Beck’s “risk society” to Douglas’s cultural theory, sociological perspectives reveal that how we define, prioritize, and respond to risks reflects deeper issues of culture, power, inequality, and trust.

In the modern world, risks are increasingly global, interconnected, and invisible, requiring not only expert systems but also participatory, equitable, and reflexive forms of governance. As societies continue to grapple with challenges such as climate change, pandemics, and technological hazards, sociology offers valuable insights into the human dimensions of risk—reminding us that how we perceive and manage uncertainty is ultimately a reflection of our social fabric itself.

Do you like this this Article ? You Can follow as on :-

Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/hubsociology

Whatsapp Channel – https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029Vb6D8vGKWEKpJpu5QP0O

Gmail – hubsociology@gmail.com

Exam-style questions on Perception and Management of Risk

5 Marks Questions on Perception and Management of Risk

- Define the sociological concept of “risk.”

- What is meant by the term “social construction of risk”?

- Mention two key features of Ulrich Beck’s “Risk Society.”

- How does media influence the perception of risk in society?

- Give two examples of how risks are unequally distributed in society.

10 Marks Questions on Perception and Management of Risk

- Discuss Mary Douglas and Aaron Wildavsky’s Cultural Theory of Risk with examples.

- Explain how globalization has increased the interdependence of risks across societies.

- Analyze the role of institutions (government, science, insurance) in managing risks.

- Discuss the relationship between risk and inequality in modern societies.

- Explain how everyday communities manage risks using informal or cultural practices.

15 Marks Questions on Perception and Management of Risk

- Critically examine Ulrich Beck’s concept of the “Risk Society.” How is it relevant in the context of modern global challenges?

- “Risk is not merely a scientific calculation but a cultural and social construct.” Discuss with sociological examples.

- Evaluate the role of media in shaping public perception of risks. How can media both amplify and minimize risks?

- How do inequality and power relations influence the perception and management of risks in society?

- Discuss the sociological dimensions of risk governance. What strategies can make risk management more reflexive, inclusive, and equitable?