Introduction

Political polarization—defined as the growing ideological distance and hostility between opposing political groups—has become one of the defining features of the 21st century. Across nations, societies have witnessed increasing divisions between left and right, liberal and conservative, secular and religious, globalist and nationalist. While this phenomenon is often analyzed through political science or communication studies, sociology offers a deeper understanding of how such divisions are rooted in social power dynamics, class structures, and legitimacy struggles.

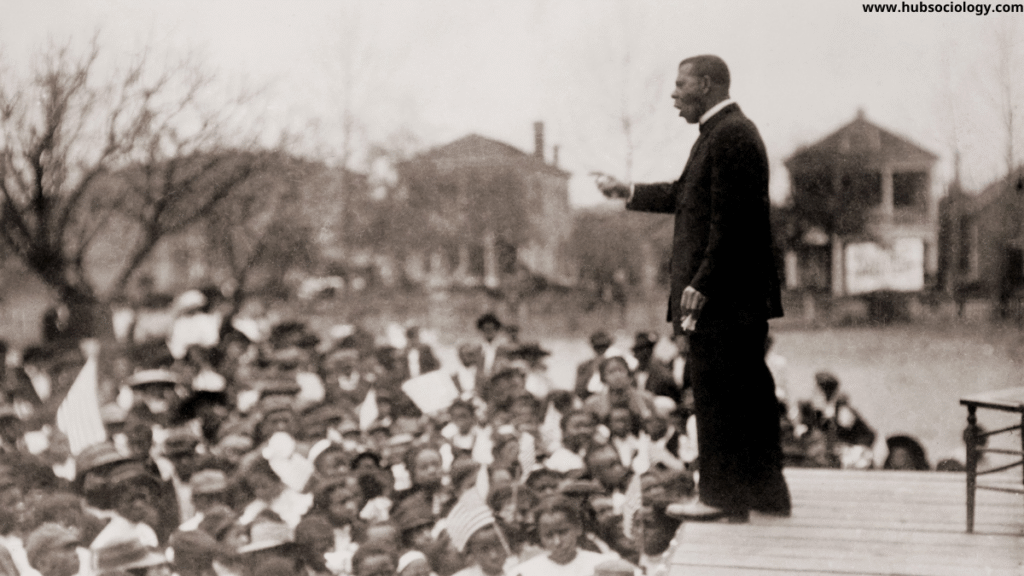

The German sociologist Max Weber (1864–1920), one of the founding figures of modern sociology, provides a particularly powerful framework for understanding political polarization. His theory of power (Macht) and authority (Herrschaft) helps explain how political leaders, institutions, and citizens negotiate legitimacy and domination in times of deep ideological conflict. In many ways, the current wave of political polarization represents Weber’s theory of power in action—a vivid demonstration of how competing claims to legitimacy can reshape democratic governance, political institutions, and civic life.

This article explores political polarization sociologically through Weber’s concepts of power, authority, and legitimacy. It analyzes how Weber’s tripartite classification of authority (traditional, charismatic, and legal-rational) manifests in polarized societies, how power struggles emerge in democratic settings, and how social stratification and identity politics intensify divisions. Finally, it considers Weber’s warnings about bureaucracy, charisma, and the “iron cage” of rationality in understanding the long-term consequences of polarization.

Understanding Political Polarization in Sociological Terms

Political polarization refers to the division of society into two or more conflicting ideological camps with limited overlap or willingness to compromise. It is not merely a political disagreement—it is a social process that transforms how citizens view morality, identity, and authority. In a polarized environment, political affiliation becomes a marker of social identity, shaping friendships, marriages, workplaces, and even consumption habits.

From a sociological perspective, polarization can be analyzed as a form of social differentiation, where groups define themselves not only by shared beliefs but by opposition to others. This mirrors Weber’s observation that power and domination are always relational—those who wield authority depend on those who consent to it, and conflict arises when legitimacy is questioned.

Polarization is not simply the presence of diverse opinions; rather, it involves the moralization of difference and the perception that the opposing side threatens the very foundation of society. In this sense, political polarization represents a struggle over meaning and legitimacy, which makes Weber’s power theory especially relevant.

Weber’s Power Theory: The Foundation

Max Weber defined power (Macht) as the ability of an individual or group to impose their will upon others, even against resistance. However, not all power is equal. For Weber, the key sociological distinction lies between power (coercive capacity) and authority (legitimate domination). Authority involves the voluntary compliance of subordinates, based on the belief that those in power have a rightful claim to rule.

Weber identified three ideal types of authority:

- Traditional authority – rooted in custom, heritage, and longstanding social orders (e.g., monarchies, aristocracies).

- Charismatic authority – based on devotion to the exceptional sanctity, heroism, or exemplary character of a leader (e.g., revolutionary figures, populist leaders).

- Legal-rational authority – founded on impersonal rules, laws, and bureaucratic systems typical of modern democracies.

Each type of authority represents a different basis of legitimacy, and political polarization often involves contests between these forms. For example, populist movements may challenge bureaucratic rationality through charisma, while traditionalists may defend inherited moral orders against progressive reforms.

Weber’s Power Theory in Action: Polarization and Competing Legitimacies

1. The Crisis of Legal-Rational Authority

Modern democracies are primarily organized around legal-rational authority. Citizens accept state power because it operates through predictable laws and institutions. However, when people lose faith in the fairness or effectiveness of these systems—whether due to corruption, inequality, or media manipulation—legal-rational legitimacy erodes.

In polarized societies, this erosion creates fertile ground for charismatic and traditional forms of authority to re-emerge. Leaders position themselves as moral saviors or defenders of the “true people” against corrupt elites and bureaucracies. Weber saw this as a recurring feature of social change: when rationalized systems become too impersonal, individuals seek meaning and authenticity through charisma.

For instance, the rise of populist leaders in various countries—such as the United States, India, Brazil, or Hungary—illustrates Weber’s idea of charismatic domination challenging bureaucratic rationality. These leaders often claim to represent the “will of the people” over institutional procedures, thereby transforming political loyalty into personal devotion.

This shift intensifies polarization because it delegitimizes institutional checks and compromises, framing them as obstacles to the people’s will. The bureaucratic state, once seen as neutral, becomes a battlefield of moral and ideological struggle.

2. Charisma and the Polarization of Belief

Weber’s concept of charisma is crucial in understanding modern political polarization. Charisma is not merely personal charm—it is a social relationship where followers attribute extraordinary qualities to a leader. In times of crisis, people crave certainty and meaning, and charismatic leaders provide it through emotional appeals, simplified narratives, and promises of renewal.

Charismatic authority thrives on crisis and conflict—it needs an “enemy” to mobilize the masses. In polarized politics, this often translates into us-versus-them rhetoric, where opposition is framed as betrayal. Social media amplifies this dynamic by creating echo chambers that reward emotional intensity and moral outrage.

Weber warned that charismatic authority is inherently unstable. Once the crisis subsides or the leader loses credibility, the legitimacy collapses unless it is institutionalized. Yet in polarized societies, charisma becomes self-perpetuating, as ongoing conflict sustains belief. Thus, Weber’s theory helps explain how charismatic politics transforms democracy into permanent mobilization, preventing consensus and compromise.

3. Traditional Authority and the Politics of Cultural Restoration

Political polarization also involves the revival of traditional authority—claims rooted in heritage, religion, or cultural identity. In many societies, movements arise that seek to restore moral orders perceived as threatened by modernization, secularism, or globalization.

From Weber’s perspective, this represents a retraditionalization of legitimacy. People turn to traditional values and identities as sources of stability amid the uncertainty of modern rationalized life. The politics of nationalism, religious revival, or “family values” are manifestations of this.

For example, in India, the growing emphasis on cultural nationalism can be seen as the assertion of traditional legitimacy in a modern democratic context. Similarly, debates over immigration and multiculturalism in Western democracies reflect struggles between traditional moral frameworks and legal-rational pluralism.

The result is a collision of legitimacy bases: traditional versus rational, moral versus procedural, faith versus bureaucracy. Polarization intensifies when these frameworks become mutually exclusive.

Weber’s Sociology of Domination and the Institutional Dimension

Weber understood domination not merely as political but as sociological—it involves institutions, social classes, and status groups that maintain or contest authority. In polarized democracies, institutions such as courts, media, and universities become symbolic battlegrounds for legitimacy.

The Bureaucratic “Iron Cage”

Weber famously described modern rationality as an “iron cage” that traps individuals in systems of calculation and control. Bureaucracy, though efficient, alienates people by reducing human values to rules and metrics. Polarization can thus be seen as a reaction to bureaucratic alienation.

Citizens who feel unheard by bureaucratic systems may rally behind charismatic or traditional leaders who promise moral clarity and emotional connection. Ironically, this rebellion often leads to even more authoritarian structures, as charisma demands loyalty over deliberation.

Class and Status Dimensions

Weber’s analysis of class, status, and party also sheds light on polarization. Class divisions create material inequalities, while status groups produce symbolic hierarchies of prestige and lifestyle. Political polarization often maps onto these social cleavages:

- Urban elites versus rural traditionalists,

- Secular professionals versus religious communities,

- Cosmopolitan youth versus conservative elders.

These social boundaries become moral boundaries, transforming socioeconomic inequality into cultural antagonism. Weber’s insight that power operates through both material and symbolic means helps explain why polarization persists even in prosperous democracies—it is not only about resources but about recognition and respect.

The Role of Media and Technology: Rationalization Meets Charisma

Weber did not live to witness the digital age, yet his theory of rationalization can be extended to understand how media technology mediates authority today. The modern information environment fuses rationalized bureaucracy (algorithms, data, surveillance) with charismatic communication (emotional storytelling, influencer culture).

Social media transforms every citizen into both subject and performer of power. Leaders bypass institutional filters and speak directly to followers, creating personalized legitimacy. At the same time, algorithms rationalize visibility, rewarding outrage and identity affirmation.

Thus, the digital age represents the fusion of Weber’s charisma and rationalization, creating a new form of domination—algorithmic charisma—where emotion and computation reinforce each other. The result is a feedback loop that deepens polarization, as opposing groups inhabit distinct moral universes shaped by digital validation.

Consequences of Polarization: From Legitimacy Crisis to Authority Collapse

From a Weberian standpoint, persistent political polarization signals a legitimacy crisis—a situation where no single form of authority commands universal acceptance. When legal-rational institutions lose trust, charismatic and traditional claims fill the vacuum, leading to institutional instability.

This crisis has several sociological consequences:

- Erosion of institutional trust: Bureaucratic and judicial institutions are viewed as partisan, undermining the legal-rational foundation of democracy.

- Personalization of politics: Leadership becomes about personality rather than policy, reinforcing the cycle of charisma and polarization.

- Moralization of conflict: Political opposition is perceived not as a legitimate competitor but as an enemy of the moral order.

- Fragmentation of public discourse: Truth becomes relative, as different social groups operate within distinct systems of meaning and legitimacy.

Weber feared that such conditions could lead to the disenchantment of politics—a loss of faith in collective rational deliberation. The outcome could be either technocratic control (the dominance of bureaucratic rationality) or authoritarian populism (the dominance of charisma)—both forms representing distortions of democratic legitimacy.

Restoring Legitimacy: A Weberian Path Forward

Weber’s sociology does not offer easy solutions, but it provides tools to diagnose the roots of polarization. The key lies in rebalancing the types of authority—restoring trust in legal-rational institutions while respecting the moral and emotional needs that charisma and tradition fulfill.

A Weberian response to polarization would involve:

- Reinvigorating procedural legitimacy: ensuring fairness, transparency, and responsiveness in democratic institutions.

- Encouraging responsible leadership: charismatic leaders must transition from personal rule to institutional stewardship.

- Promoting civic education: citizens must understand the distinction between power and authority, emotion and legitimacy.

- Building pluralistic narratives: societies must allow coexistence of different values without moral absolutism.

Sociologically, the challenge is to transform conflict into legitimate competition, where power struggles occur within shared norms rather than destroy them. Weber understood that modern politics is always a “vocation”—a struggle for meaning and responsibility in a disenchanted world.

Conclusion

Political polarization, far from being a purely political issue, is a sociological manifestation of Weber’s theory of power in action. It reveals the tensions between authority and legitimacy, bureaucracy and charisma, rationalization and emotion. In modern democracies, the erosion of legal-rational legitimacy has opened space for charismatic and traditional forms of domination, producing deep ideological divides.

Through Weber’s lens, polarization appears not as an anomaly but as a symptom of modernity’s contradictions. The rationalized world demands efficiency and neutrality, yet human beings crave meaning, belonging, and moral clarity. When these needs are unmet, they turn to charismatic or traditional sources of authority, often in opposition to democratic institutions.

Ultimately, Weber’s insights remind us that the fate of democracy depends not only on rules and institutions but on the sociology of belief—on the ability of societies to sustain legitimacy amid conflict. Political polarization, therefore, is not just a test of governance but a mirror of our collective struggle between reason and faith, order and passion, power and legitimacy.

Do you like this this Article ? You Can follow as on :-

Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/hubsociology

Whatsapp Channel – https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029Vb6D8vGKWEKpJpu5QP0O

Gmail – hubsociology@gmail.com

10 FAQs on Political Polarization

1. What is Political Polarization in sociology?

Answer:

Political polarization refers to the deepening division of society into opposing ideological groups that differ not just in opinion but in worldview, moral values, and social identity. In sociology, it is seen as a process where power, legitimacy, and group identity become sources of social conflict.

2. How does Max Weber’s Power Theory explain Political Polarization?

Answer:

Weber’s Power Theory explains polarization as a clash of legitimacy forms—legal-rational, traditional, and charismatic authority. When bureaucratic systems lose trust, charismatic and traditional leaders rise, intensifying division and emotional politics.

3. What are the three types of authority according to Weber?

Answer:

Weber identified:

- Traditional authority – based on customs and heritage.

- Charismatic authority – based on devotion to a leader’s exceptional qualities.

- Legal-rational authority – based on rules and laws.

Political polarization often arises from tensions among these three types.

4. How does charismatic leadership contribute to Political Polarization?

Answer:

Charismatic leaders gain power through emotional appeal and crisis narratives. They often use “us versus them” rhetoric, which deepens divisions and undermines rational deliberation. Weber saw this as charisma overpowering institutional authority.

5. What role does bureaucracy play in Political Polarization?

Answer:

Weber described bureaucracy as the “iron cage” of rationality—efficient but impersonal. When citizens feel alienated by bureaucratic systems, they reject them in favor of charismatic or traditional authority, leading to polarized politics.

6. How do traditional values influence Political Polarization?

Answer:

Traditional authority revives during periods of cultural or moral anxiety. Movements rooted in religion, nationalism, or heritage can challenge modern liberal systems, creating divisions between traditionalist and progressive social groups.

7. What is a legitimacy crisis in Political Polarization?

Answer:

A legitimacy crisis occurs when citizens lose faith in political institutions and no single form of authority commands universal trust. Polarization accelerates this crisis, as each side views the other as morally illegitimate.

8. How does social media intensify Political Polarization?

Answer:

Social media merges Weber’s ideas of charisma and rationalization—emotional communication through algorithmic systems. It amplifies outrage, rewards identity politics, and isolates users into echo chambers that reinforce polarized beliefs.

9. How can societies reduce Political Polarization according to Weber’s theory?

Answer:

Weberian solutions include restoring trust in legal-rational authority, promoting responsible leadership, and encouraging civic education that differentiates between emotional appeal and legitimate governance.

10. Why is Political Polarization considered a sociological phenomenon?

Answer:

Because it extends beyond politics into social identities, cultural norms, and institutional trust. Weber’s sociology shows that polarization reflects deeper struggles over meaning, morality, and the rightful sources of authority in society.

5 thoughts on “Political Polarization: Weber’s Power Theory in Action”