Introduction on Gram Sabha to Sammaan

The landscape of rural India has been historically defined by a rigid social hierarchy, where power, resources, and voice were concentrated in the hands of a few dominant castes and classes. The constitutionalization of the Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs) through the 73rd Amendment Act of 1992 was not merely an administrative reform; it was a profound sociological experiment. It aimed to dismantle centuries-old structures of oppression by legally mandating the decentralization of political power to the village level.

This article delves into the complex sociological dynamics of how PRIs have functioned as both an instrument and an arena for the empowerment of India’s weaker sections—Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), and Women—exploring the transformative changes, persistent challenges, and the ongoing renegotiation of social power in village India.

Table of Contents on Gram Sabha to Sammaan

The 73rd Amendment: A Structural Framework for Inclusion

From a sociological standpoint, the 73rd Amendment’s genius lies in its attempt to engineer social change through political structure. It moved beyond idealism to provide a concrete, legally-backed mechanism for inclusion.

- Mandatory Reservations: The amendment mandated the reservation of seats in all three tiers of PRIs (Gram Panchayat, Panchayat Samiti, and Zila Parishad) for SCs and STs in proportion to their population. Crucially, it also reserved not less than one-third of all seats for women, including within the SC/ST quotas. This provision forced a demographic representation that was previously unthinkable in the traditional caste panchayats, which were exclusive and often oppressive.

- The Gram Sabha as a Sovereign Body: The Amendment established the Gram Sabha (village assembly of all adult members) as the cornerstone of the system. Sociologically, this created a new public sphere—a space where, in theory, every villager, regardless of caste or gender, had the right to participate in decision-making, approve development plans, and hold elected representatives accountable. This was a direct challenge to the private, caste-based deliberations that had traditionally governed village life.

Empowerment in Practice: Shifts in the Social Fabric

The implementation of PRIs over the last three decades has triggered significant, albeit uneven, sociological shifts.

1. Political Empowerment and the Emergence of New Leadership

The most visible impact has been the creation of a new class of leaders from marginalized communities. For the first time, individuals from SC, ST, and women backgrounds have gained access to formal positions of power—the title of Sarpanch (village head). This has two key effects:

- Symbolic Empowerment: The mere presence of a Dalit Sarpanch or a woman Pradhan challenges deep-seated social norms. It serves as a powerful symbol, demonstrating that authority is not the birthright of the upper castes. This can shatter psychological barriers and inspire younger generations.

- Substantive Empowerment: These elected representatives gain control over local resources and development funds. They influence the selection of beneficiaries for housing schemes (like PMAY), pensions, and employment programs (MGNREGA). This control over economic resources is a critical tool for altering patronage networks that traditionally reinforced dependency on dominant groups.

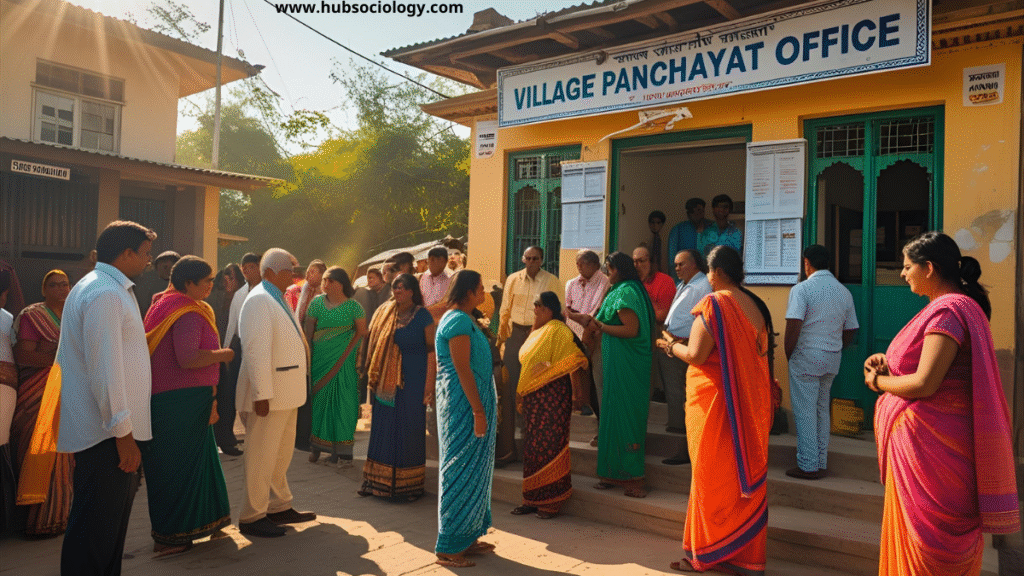

2. The Quiet Revolution: Women in the Panchayat

The reservation for women has perhaps been the most disruptive and studied sociological aspect of PRIs.

- From the Private to the Public Sphere: It has forced a massive entry of women into the public, political domain—a space from which they were largely excluded. Initially, many faced the “proxy” or “puppet” phenomenon, where male relatives (husbands, fathers-in-law) exerted control. However, over time, many women have overcome social barriers, gained confidence, and started exercising their agency independently.

- Shifting Policy Priorities: Sociological studies have shown that women leaders often prioritize issues previously neglected in male-dominated governance, such as drinking water, sanitation, childcare (anganwadis), domestic violence, and girl’s education. This re-gendering of the development agenda addresses the core needs of the community more holistically.

- Intra-Household Dynamics: A woman’s role as an elected representative can alter power dynamics within her own household. Her increased mobility, interaction with officials, and control over resources can lead to greater autonomy and decision-making power within the family, challenging patriarchal structures at the micro-level.

3. Assertion of Dignity and Rights

For Dalits and Adivasis, PRIs have provided a platform to assert their citizenship rights. The Gram Sabha offers a formal forum to raise grievances—be it about the distribution of resources, access to common land, or cases of social discrimination and violence. While the process is fraught with conflict, the very act of speaking up in a constituted authority challenges the culture of silence and impunity enjoyed by dominant castes. This is a slow but crucial process of moving from a state of supplication to a state of negotiation and assertion.

Persistent Challenges: The Gap Between Law and Society

Despite the progressive legal framework, the empowerment process is severely constrained by the resilience of traditional social structures. Sociology helps us understand why the law’s intent often falters on the rocky terrain of social reality.

- Elite Capture and Proxy Rule: The entrenched rural elite often finds ways to subvert the spirit of reservations. They may use intimidation, violence, or economic coercion to control elected representatives from weaker sections. The phenomenon of “Sarpanch-Pati” (husband of the woman Sarpanch) is a classic example of how patriarchy adapts to new laws to maintain control.

- Social Boycott and Violence: Elected representatives from marginalized communities, especially those who assert their authority, often face severe social ostracization, verbal abuse, and even physical violence. Dominant castes perceive their loss of monopoly over power as a threat to the entire social order and retaliate to maintain their hegemony.

- Lack of Administrative and Financial Autonomy: PRIs are often hamstrung by a lack of genuine devolution of functions, functionaries, and funds (the 3 Fs) from state governments. The local bureaucracy, which may still be influenced by caste biases, can obstruct the work of elected representatives, making it difficult for them to implement their agendas.

- Internalized Hierarchies: Empowerment is not just an external process; it is also internal. Centuries of socialization into accepting a subordinate status can inhibit elected members from acting assertively. Lack of education, political experience, and confidence further compounds this problem, making them dependent on upper-caste officials or relatives.

Conclusion on Gram Sabha to Sammaan

The Panchayati Raj Institutions represent a watershed moment in the sociological history of rural India. They have irrevocably altered the political map of the village, injecting a dose of democracy into its deeply hierarchical veins. They have created cracks in the edifice of caste and patriarchy, allowing light and agency to filter through to those who were perpetually in the shadows.

However, to view PRIs as an unqualified success would be a sociological misdiagnosis. They are better understood as a contested terrain—a battleground where a slow, grinding war for social change is being waged. The law provided the weapons (reservations, Gram Sabha), but the outcome of each battle is determined by local power equations, caste configurations, and the courage of individuals.

The true empowerment of weaker sections through PRIs is not measured solely by the number of elected representatives, but by their ability to exercise power independently, to reorient development priorities, and to command respect (sammaan) not out of fear, but out of rightful authority. This requires a continuous effort beyond the political structure—including social movements, education, economic upliftment, and legal support—to strengthen the hands of those who dare to represent the marginalized. The Panchayati Raj, therefore, remains India’s most ambitious and ongoing experiment in social engineering, its final chapter yet to be written.

Do you like this this Article ? You Can follow as on :-

Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/hubsociology

Whatsapp Channel – https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029Vb6D8vGKWEKpJpu5QP0O

Gmail – hubsociology@gmail.com

Topic Related Questions on Gram Sabha to Sammaan

5 Marks Questions on Gram Sabha to Sammaan (Short Answer)

- Define the term ‘Proxy Rule’ in the context of Panchayati Raj Institutions.

- List any three provisions of the 73rd Amendment Act that aim to empower weaker sections.

- What is the sociological significance of the Gram Sabha?

- How has the reservation for women in PRIs altered the development agenda in villages?

- Briefly explain the concept of ‘Elite Capture’ concerning Panchayati Raj.

- Differentiate between symbolic and substantive empowerment in the context of a Dalit Sarpanch.

- What is meant by the ‘Sarpanch-Pati’ phenomenon?

- Name two key challenges faced by women representatives in Panchayats.

- How do PRIs provide a platform for the assertion of dignity for Scheduled Castes?

- Why are PRIs considered a form of social engineering?

10 Marks Questions on Gram Sabha to Sammaan (Detailed Answer)

- Analyze the role of the 73rd Constitutional Amendment Act in dismantling traditional power structures in rural India.

- “The Gram Sabha is the cornerstone of the Panchayati Raj system.” Discuss this statement from a sociological perspective.

- Examine the impact of political reservations for women on the patriarchal structure of Indian villages.

- How do Panchayati Raj Institutions facilitate both political and social empowerment for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes? Illustrate with examples.

- Critically evaluate the phenomenon of ‘Elite Capture’ as a major impediment to the empowerment of weaker sections through PRIs.

- Discuss the ways in which elected women representatives in PRIs have re-gendered local development priorities.

- “Empowerment through PRIs is not just external but also internal.” Explain this statement in the context of overcoming internalized hierarchies.

- To what extent have PRIs been successful in creating a new class of leadership from among the weaker sections of rural society?

- Social boycott and violence are tools used to maintain hegemony. Analyze this statement in the context of resistance faced by marginalized representatives in PRIs.

- Compare and contrast the symbolic and substantive aspects of empowerment achieved through reservations in Panchayati Raj Institutions.

15 Marks Questions on Gram Sabha to Sammaan (Essay/Long Answer)

- Panchayati Raj Institutions were envisioned as instruments of social transformation. Critically analyze their role in the empowerment of weaker sections in village India, highlighting the gap between legal intent and social reality.

- The reservation policy for SCs, STs, and women in PRIs has triggered a silent revolution in the rural social structure. Discuss the nature and extent of this revolution, citing the achievements and persistent challenges.

- “PRIs are a contested terrain where a slow war for social change is being waged.” Elaborate on this statement by examining the dynamics of power, resistance, and assertion between dominant and marginalized groups in the Panchayati Raj framework.

- Evaluate the impact of women’s participation in Panchayati Raj Institutions on both the public sphere of village governance and the private sphere of the household.

- From a sociological perspective, assess how Panchayati Raj Institutions have functioned as an ‘arena’ for conflict and an ‘instrument’ for change in the lives of India’s rural weaker sections.