Introduction on Hazards and Disasters

Hazards and disasters are often understood in terms of physical destruction, economic loss, or environmental degradation. However, they are also profoundly social phenomena. While a hazard refers to a potential threat arising from natural or human-induced causes, a disaster occurs when that hazard interacts with human vulnerability and social structures, leading to widespread disruption. Sociology provides a crucial lens to understand these phenomena by examining how social organization, inequality, culture, and institutions shape both the causes and consequences of hazards and disasters.

This article explores hazards and disasters in a sociological aspect, highlighting their social construction, impact on communities, role of inequality, collective responses, and broader implications for society.

Understanding Hazards and Disasters

Hazards

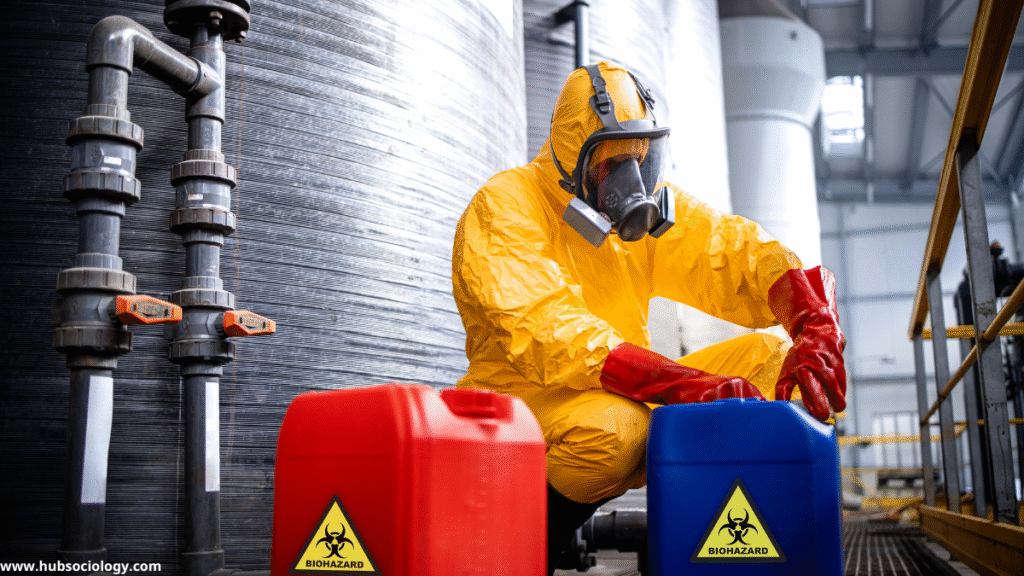

Hazards are potential sources of harm that may arise from natural processes like earthquakes, floods, cyclones, or from human activities such as industrial accidents, nuclear leakage, and environmental pollution. A hazard in itself does not necessarily become a disaster unless it interacts with vulnerable human populations.

Disasters

A disaster is the actual materialization of a hazard, leading to large-scale destruction, disruption, and social disorganization. Disasters cannot be understood solely as physical events; they are shaped by human preparedness, resource distribution, and institutional responses. For example, an earthquake of similar magnitude may be disastrous in one society but manageable in another, depending on infrastructure, governance, and social resilience.

The Sociological Construction of Disasters

Sociologists argue that disasters are not just “natural” events but are socially constructed. This means their effects depend heavily on human arrangements:

- Urban planning and development: Poorly designed housing in earthquake-prone areas increases risks.

- Economic structures: Marginalized populations often inhabit floodplains or unsafe settlements due to lack of alternatives.

- Cultural practices: Traditional beliefs and community networks may influence disaster responses positively (through solidarity) or negatively (through fatalism).

- Governmental policies: Preparedness, disaster management strategies, and relief distribution play a decisive role in shaping outcomes.

Thus, disasters are as much about society as they are about nature.

Vulnerability and Inequality on Hazards and Disasters

A central sociological concept in disaster studies is vulnerability. Vulnerability refers to the degree to which individuals or groups are at risk from hazards due to social, economic, or political disadvantages.

- Class and Economic Status:

Poor households often lack resources to build resilient homes, access insurance, or recover quickly after a disaster. For example, slum dwellers in urban areas are disproportionately affected by floods. - Caste, Ethnicity, and Marginalization:

In many societies, marginalized groups receive less attention in disaster relief. Their access to aid and rehabilitation is often shaped by systemic discrimination. - Gender:

Women and children are more vulnerable in disasters due to social roles, caregiving responsibilities, and limited mobility. In patriarchal societies, women may face additional risks of exploitation during relief and rehabilitation. - Age and Disability:

The elderly and differently-abled individuals face unique challenges during evacuation, shelter, and post-disaster adaptation.

From a sociological angle, disasters expose and amplify existing inequalities.

Community and Collective Response

Disasters often disrupt the normal functioning of society but also generate strong forms of solidarity and cooperation. Sociologists study how communities respond collectively to hazards:

- Social Solidarity: Communities often come together during disasters, sharing resources and offering mutual support. This reflects Émile Durkheim’s idea of collective conscience.

- Role of Civil Society: NGOs, local associations, and religious groups play critical roles in mobilizing relief and rebuilding efforts.

- Informal Networks: Family ties, kinship, and neighborhood relations influence how quickly people receive help.

- Mistrust and Conflict: In some cases, disasters also lead to competition over scarce resources, social unrest, or scapegoating of marginalized groups.

Thus, disasters test both the resilience and fragility of social bonds.

Culture, Perception and Risk on Hazards and Disasters

Hazards and disasters are also shaped by cultural perceptions of risk:

- Belief Systems: Some communities interpret disasters as divine punishment or fate, which influences preparedness and coping strategies.

- Risk Perception: Urban populations may underestimate certain risks (like heatwaves) while overestimating others (like rare tsunamis).

- Media Influence: The way disasters are represented in mass media affects public perception, state response, and international aid.

Sociology emphasizes that disasters are not experienced uniformly; cultural meanings play a role in how people interpret and respond to them.

Institutional Role and Governance

Disaster management is deeply tied to institutions:

- State and Government: The capacity of governments to provide early warning systems, evacuations, relief distribution, and rehabilitation shapes disaster outcomes. Weak governance often worsens the crisis.

- International Organizations: Bodies like the UN, Red Cross, and World Health Organization provide cross-border assistance and frameworks for disaster risk reduction.

- Legal Frameworks: Laws regulating construction, land use, and industrial safety are essential to mitigate hazards. Non-compliance often turns hazards into disasters, as seen in industrial accidents like the Bhopal gas tragedy.

Institutional responses highlight how social structures mediate the relationship between hazards and human suffering.

Disasters as Agents of Social Change

While disasters bring destruction, they also act as catalysts for social change. Sociologists identify both positive and negative consequences:

- Positive:

- Strengthened community bonds.

- Policy reforms in disaster management.

- Awareness of environmental protection and sustainable development.

- Negative:

- Deepened inequalities.

- Long-term displacement and cultural loss.

- Rise of authoritarian governance under the guise of emergency measures.

Disasters, therefore, are not merely interruptions but events that reshape the social fabric.

Case Illustrations on Hazards and Disasters

- The 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami:

Beyond physical destruction, the tsunami exposed vulnerabilities of coastal fishing communities, unequal relief distribution, and the role of international aid. - The Bhopal Gas Tragedy (1984):

This industrial disaster revealed negligence of corporations, weak state regulation, and long-term health consequences for marginalized groups, making it a sociological landmark. - COVID-19 Pandemic:

The pandemic was both a hazard and a disaster, magnifying global inequalities. Access to healthcare, digital education, and livelihood security revealed how disasters are socially stratified. - Hurricane Katrina (2005, USA)

The hurricane showed stark racial and class inequalities, as African-American and low-income populations in New Orleans faced greater vulnerability and slower recovery. - Chernobyl Nuclear Disaster (1986, USSR/Ukraine)

A technological hazard turned catastrophic, leading to displacement, long-term health impacts, and state secrecy that eroded public trust in governance. - Cyclone Nargis (2008, Myanmar)

Government censorship and weak institutional response worsened the humanitarian crisis, highlighting the role of governance in disaster management. - The Gujarat Earthquake (2001, India)

Thousands of deaths and mass displacement revealed the vulnerability of poor housing structures, while caste and community affiliations shaped relief distribution. - Fukushima Nuclear Disaster (2011, Japan)

Triggered by an earthquake and tsunami, the crisis raised questions about technological safety, government accountability, and long-term displacement. - Australian Bushfires (2019–2020)

These fires showed how climate change interacts with human settlement patterns, while Indigenous fire management practices received new recognition. - Haiti Earthquake (2010)

The massive earthquake devastated an already impoverished nation, exposing global inequalities in aid distribution and the long-term dependency created by external relief agencies.

Toward a Sociological Understanding of Disaster Preparedness

A sociological approach emphasizes that disaster preparedness must go beyond technical measures to address social dimensions:

- Reducing Inequality: Ensuring marginalized groups have equal access to resources and safety.

- Strengthening Community Networks: Local participation in planning and response increases resilience.

- Integrating Cultural Knowledge: Respecting traditional practices while introducing modern preparedness measures.

- Promoting Social Justice: Relief and rehabilitation must prioritize the most vulnerable to avoid reproducing inequalities.

Preparedness is as much about social arrangements as it is about technology.

Conclusion on Hazards and Disasters

Hazards and disasters cannot be fully understood without recognizing their sociological dimensions. They are not simply natural or technical events but deeply social processes shaped by inequality, culture, governance, and collective behavior. While hazards may be inevitable, disasters are not—they emerge from the interaction between threats and human vulnerability. A sociological perspective highlights that reducing disaster risk requires addressing structural inequalities, fostering social solidarity, and building resilient communities.

Ultimately, hazards and disasters serve as mirrors reflecting the strengths and weaknesses of societies. By studying them sociologically, we gain insights not only into survival but also into the pursuit of a more just and resilient social order.

Do you like this this Article ? You Can follow as on :-

Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/hubsociology

Whatsapp Channel – https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029Vb6D8vGKWEKpJpu5QP0O

Gmail – hubsociology@gmail.com

Topic related question on Hazards and Disasters

5 Marks Questions on Hazards and Disasters

- Define the term “hazard” in a sociological sense.

- Differentiate between hazard and disaster with examples.

- What is vulnerability in the context of disasters?

- Give two examples of man-made hazards.

- State two ways in which inequality increases disaster risk.

10 Marks Questions on Hazards and Disasters

- Explain how disasters are socially constructed phenomena.

- Discuss the role of culture and beliefs in shaping disaster responses.

- How do class and gender influence vulnerability during disasters?

- Examine the role of government institutions in disaster management.

- Explain the sociological significance of community solidarity in post-disaster recovery.

15 Marks Questions on Hazards and Disasters

- Critically analyze the relationship between hazards, disasters, and social inequality.

- Discuss with examples how disasters act as agents of social change.

- Evaluate the role of media and communication in shaping public perception of disasters.

- “Disasters are not purely natural; they reflect human vulnerability and governance failure.” Elaborate with examples.

- Using sociological theories, analyze the collective behavior of communities in times of disaster.