Introduction on Islam and Secularism in Central Asian Societies

Central Asia, comprising Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, represents one of the most fascinating laboratories for studying the coexistence of religion and secularism. The region, situated at the crossroads of Islamic civilization, Soviet socialism, and post-Soviet nation-building, reflects complex social dynamics where Islam and secularism are not merely ideological concepts but lived realities shaping identity, governance, and everyday practices. From the nomadic traditions of the steppe to the Soviet experiment in state atheism, and from the post-independence revival of Islamic identity to contemporary struggles with global Islamist movements, Central Asian societies have continually negotiated the balance between religious faith and secular authority.

From a sociological standpoint, Islam and secularism in Central Asia are not just oppositional forces but interwoven elements that influence culture, politics, socialization, and national identity. This article explores how Central Asian societies navigate this relationship, paying attention to history, social institutions, generational differences, and global influences.

Table of Contents

Historical Context: Islam and Secularism in Soviet

Islam in Pre-Soviet Central Asia

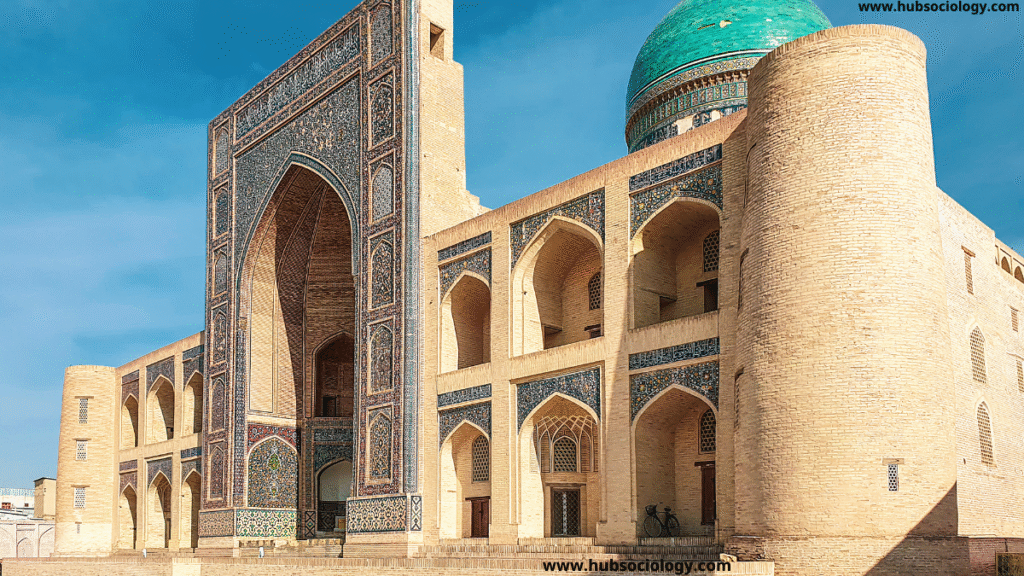

Islam entered Central Asia between the 7th and 9th centuries through Arab conquests and gradually became embedded in local societies. Over centuries, Islam influenced art, law, education, and social organization. The region produced great Islamic scholars such as al-Bukhari, al-Tirmidhi, and Avicenna, whose works shaped Islamic jurisprudence and philosophy.

However, Islam in Central Asia historically displayed a syncretic character. Alongside orthodox Sunni Islam (mostly Hanafi school), local practices integrated Sufi traditions and pre-Islamic customs, reflecting the adaptability of religion to social and cultural conditions.

Soviet Secularism and State Atheism

With the incorporation of Central Asia into the Soviet Union in the early 20th century, secularism was imposed through radical state policies. Religion was cast as “backward” and “superstitious,” and the Soviet regime implemented:

- Closure of mosques and madrasas

- Suppression of Islamic scholars and clergy

- State-promoted atheism through schools and cultural institutions

- Replacement of Islamic legal traditions with socialist law

While Islam was never eradicated, it was pushed into the private sphere and practiced discreetly. This Soviet-style secularism was not liberal separation of religion and state but rather a militant atheism that sought to control spiritual life as part of its ideological project.

Post-Soviet Revival of Islam

The collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 triggered an unprecedented revival of Islamic practices and identities. With independence, the new Central Asian republics sought cultural anchors distinct from the Soviet past, and Islam became a crucial resource for nation-building.

Key features of the revival include:

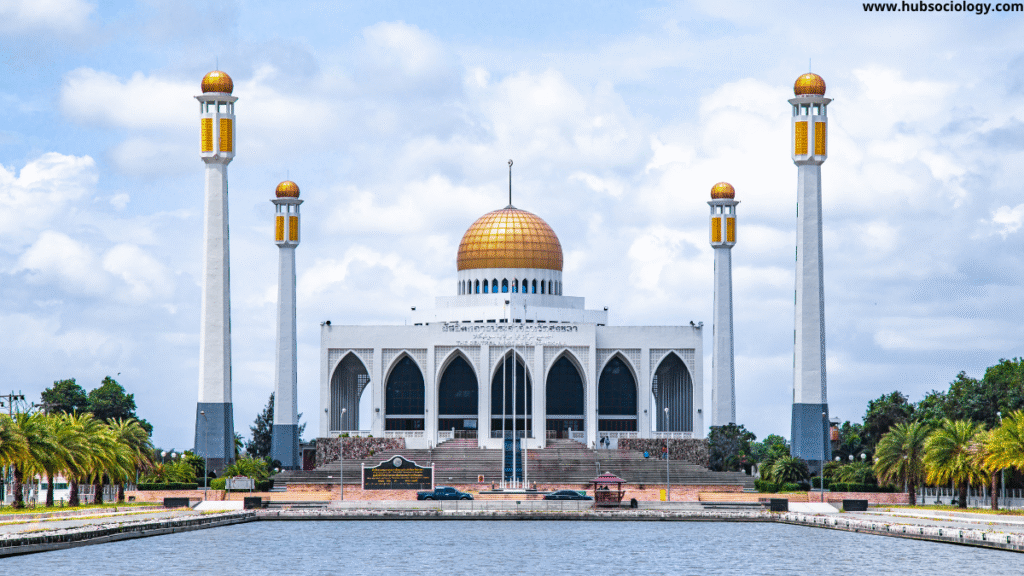

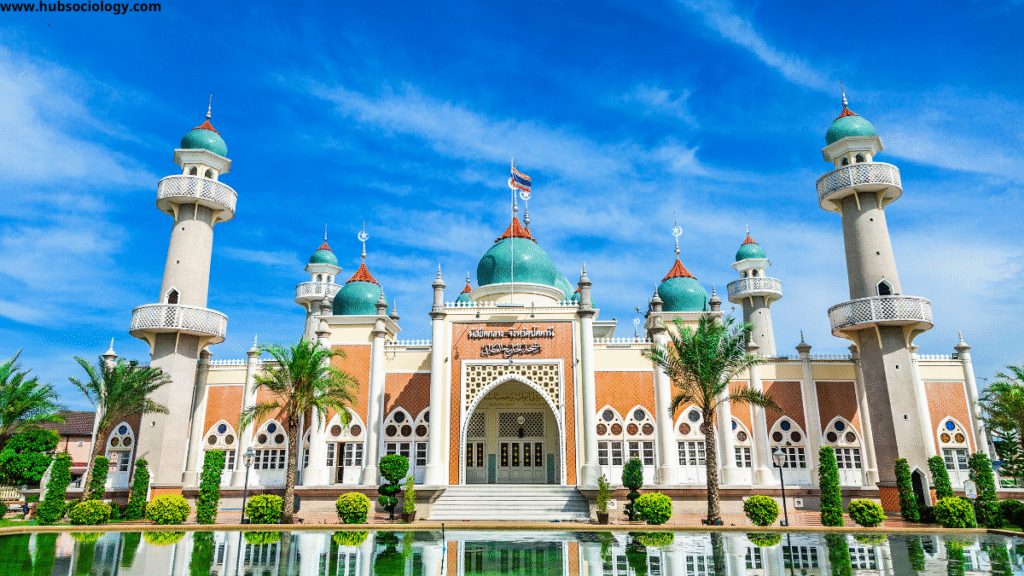

- Reopening of Mosques and Madrasas – Thousands of mosques were built across the region, often funded by foreign donors.

- Religious Education – Young people traveled abroad to study Islam, especially in Turkey, Pakistan, and the Middle East.

- Cultural Re-Islamization – Rituals such as circumcision, Islamic weddings, and funerals gained public visibility.

- State Sponsorship of Moderate Islam – Governments encouraged a “national” version of Islam tied to heritage while rejecting “imported” radical ideologies.

Yet, this revival was accompanied by state anxiety over political Islam, given fears of extremism and instability. Thus, Islam’s return was managed and framed within secular national projects.

The Sociology of Secularism in Central Asia

Secularism in Central Asia today is not identical to Western liberal secularism. Instead, it has unique features shaped by history and politics:

- State-Centric Secularism: Governments retain control over religious institutions through state religious committees, licensing of clergy, and restrictions on foreign Islamic influence.

- Instrumental Secularism: Secularism is used as a tool for political legitimacy, especially by authoritarian leaders who present themselves as protectors of stability against extremism.

- Hybrid Secularism: While official ideology is secular, religious symbols and narratives are often incorporated into national identity. For example, Uzbek leaders celebrate Islamic scholars like al-Bukhari as part of cultural heritage.

From a sociological viewpoint, secularism in Central Asia represents not simply a separation of religion and politics but a mode of governance that regulates the role of Islam in society while allowing selective cultural expression.

Social Institutions and the Balance Between Islam and Secularism

Family and Gender

In Central Asian societies, the family remains a central institution where Islam plays a visible role. Practices such as marriage rituals, funeral rites, and naming ceremonies are deeply influenced by Islamic tradition. However, secular influences—especially from the Soviet era—have left lasting marks, such as higher female literacy, women in the workforce, and legal equality.

The sociological tension arises in gender roles: younger generations sometimes embrace more conservative Islamic interpretations, while older generations recall Soviet-era secular gender norms. This creates intergenerational debates over dress codes, women’s participation in public life, and family authority.

Education

Educational systems in Central Asia remain largely secular, reflecting Soviet legacies. However, private Islamic schools and foreign-funded institutions (such as Turkish lycées in the 1990s) have introduced new forms of religious education. Governments restrict Islamic schooling to prevent radicalization, reflecting their control over the religion–education nexus.

Politics and Civil Society

Islam is a key mobilizing force in civil society, yet states strictly limit Islamic political parties. Movements like the Islamic Renaissance Party of Tajikistan (IRPT), once influential, faced bans due to concerns over extremism. Civil associations, however, often use Islamic discourse in charity, moral reform, and community building. This dual reality—religion as grassroots solidarity vs. state fear of opposition—defines the sociological role of Islam in politics.

Generational Perspectives

Sociologically, one must examine how different generations relate to Islam and secularism:

- Elder Generation (Soviet Socialization): Many older people grew up under Soviet atheism, practicing Islam only privately. They often hold pragmatic, non-political attitudes toward religion.

- Middle Generation (Post-Independence Adults): This group witnessed the Islamic revival of the 1990s. They are more exposed to both secular nation-building ideologies and transnational Islamic currents.

- Youth (Globalized Generation): Today’s young people engage with Islam through digital media, online sermons, and global Islamic movements. They face a unique identity crisis between secular modernity, consumer culture, and religious revival.

These generational differences highlight the dynamic and contested nature of religious identity in Central Asia.

Globalization, Radicalization and State Responses

The rise of global Islamic movements has deeply affected Central Asia. Transnational networks, online preaching, and exposure to Middle Eastern ideologies have introduced Salafism and other conservative trends, challenging traditional Hanafi and Sufi practices.

In response, governments employ secular frameworks to regulate Islam:

- Strict Religious Laws: Limiting mosque attendance by minors, restricting foreign funding of religious groups, and licensing sermons.

- Surveillance: Monitoring imams, religious schools, and online platforms.

- Promotion of “Traditional Islam”: States endorse a localized, apolitical version of Islam, presenting it as compatible with secular governance.

Sociologically, this reflects a negotiation between state-led secularism and grassroots religiosity, where both sides seek legitimacy but also clash over definitions of authenticity.

Islam and Secular National Identity

One of the paradoxes in Central Asia is that secular states often use Islam as a cultural marker of national identity. For example:

- Kazakhstan promotes a “multiethnic secular nation” but highlights Islamic heritage alongside Turkic traditions.

- Uzbekistan celebrates Islamic scholars while restricting Islamic political activism.

- Tajikistan recognizes Islam as central to cultural identity yet bans Islamic parties.

Thus, Islam serves as a symbol of cultural authenticity and anti-colonial identity (against the Soviet past), while secularism provides the legal-political framework of governance.

Sociological Theories and Interpretations

Several sociological theories help explain Islam–secularism dynamics in Central Asia:

- Secularization Theory: While Soviet secularism reduced public religion, post-independence revival shows that religion resurfaces under new conditions, challenging the linear secularization thesis.

- Civil Religion (Robert Bellah): In Central Asia, Islam functions as a civil religion, offering cultural cohesion without necessarily dominating politics.

- Post-Colonial Theory: The Soviet secular legacy can be interpreted as a colonial imposition, and the Islamic revival represents a form of cultural decolonization.

- Multiple Modernities (Shmuel Eisenstadt): Central Asia illustrates how modernity does not entail Western-style secularism but hybrid models where religion and secularism coexist.

Challenges and Future Directions

- Extremism vs. Moderation: States struggle to prevent radicalization while respecting religious freedoms.

- Youth Identity Crisis: Younger generations negotiate between secular education, global consumerism, and religious belonging.

- Gender Tensions: Balancing secular legal equality with rising conservative Islamic practices remains a sociological challenge.

- State Legitimacy: Overuse of secular repression may alienate believers, while overemphasis on Islam risks politicization.

The future of Islam and secularism in Central Asia will depend on whether states and societies can establish a sustainable balance where religious identity enriches cultural life without undermining secular governance.

Conclusion on Islam and Secularism in Central Asian Societies

Islam and secularism in Central Asia are not binary opposites but deeply entangled forces shaping social life. Islam provides cultural continuity, moral frameworks, and identity, while secularism—rooted in Soviet legacies and authoritarian governance—provides political order and state legitimacy. From a sociological perspective, this coexistence is characterized by negotiation, hybridity, and contestation rather than outright conflict.

Central Asia demonstrates that secularism need not erase religion, and Islam need not dominate politics; instead, both can coexist in dynamic equilibrium, producing a unique societal model distinct from both Western liberal secularism and Middle Eastern Islamist politics. Ultimately, the sociological study of Islam and secularism in Central Asia reveals not only the resilience of faith under state pressure but also the adaptability of secular authority in religiously rooted societies.

Do you like this this Article ? You Can follow as on :-

Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/hubsociology

Whatsapp Channel – https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029Vb6D8vGKWEKpJpu5QP0O

Gmail – hubsociology@gmail.com

Exam-style question on Islam and Secularism in Central Asian Societies

5 Marks Questions (Short Answer)

- Briefly explain the historical role of Islam in pre-Soviet Central Asia.

- What were the main features of Soviet secularism in Central Asia?

- Define “state-centric secularism” in the context of Central Asian societies.

- Mention two ways in which Islam re-emerged in Central Asia after independence.

- How does Islam act as a marker of national identity in post-Soviet Central Asia?

10 Marks Questions (Medium Answer)

- Discuss the impact of Soviet secularism on Islamic practices in Central Asia.

- How do family and gender roles reflect the tension between Islam and secularism in Central Asia?

- Explain the role of education in shaping the balance between Islam and secularism.

- Analyze the differences between generational attitudes toward religion and secularism in Central Asia.

- How do Central Asian governments attempt to balance the revival of Islam with fears of extremism?

15 Marks Questions (Long Answer/Essay Type)

- Critically analyze the sociological relationship between Islam and secularism in post-Soviet Central Asia.

- Using relevant sociological theories, explain how Central Asian societies illustrate the concept of “multiple modernities.”

- Discuss the role of globalization and transnational Islamic movements in reshaping Islamic identity in Central Asia.

- Evaluate how secular states in Central Asia simultaneously restrict and promote Islam as part of national identity formation.

- Examine the future challenges in balancing secular governance and Islamic revival in Central Asian societies.