Introduction

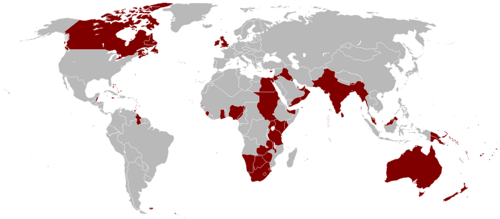

The discipline of social anthropology emerged in England during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, deeply intertwined with the expansion and consolidation of British colonialism. As European powers, particularly Britain, extended their empires across Africa, Asia, and the Americas, there arose a need to understand the cultures, social structures, and governance systems of the colonized peoples. This necessity was not merely academic but also political and administrative, as colonial rulers sought effective ways to manage and control indigenous populations.

Social anthropology, as it developed in England, was shaped by colonial imperatives, ethnographic encounters, and evolving theoretical frameworks. This article examines the relationship between colonialism and the emergence of social anthropology in England, analyzing how colonial interests influenced anthropological methodologies, theories, and institutional developments. It also explores critiques of anthropology’s colonial legacy and its transformation into a more self-reflective and critical discipline in the postcolonial era.

Colonialism and the Need for Knowledge

The British Empire, at its height, governed vast territories with diverse cultures, languages, and social systems. Colonial administrators faced challenges in ruling populations whose customs and governance structures were often radically different from European models. To facilitate effective governance, colonial officials required systematic knowledge of indigenous societies. This demand for knowledge led to the institutionalization of anthropology as an academic discipline.

Early anthropologists, often working in collaboration with colonial governments, conducted ethnographic studies to document kinship systems, political organizations, religious practices, and economic structures of colonized peoples. Figures like Sir James Frazer, Bronisław Malinowski, and A.R. Radcliffe-Brown played pivotal roles in shaping British anthropology, developing methodologies that emphasized fieldwork and functionalist interpretations of societies.

The Role of Early Anthropologists and Colonial Administration

1. James Frazer and Evolutionary Anthropology

Sir James Frazer’s The Golden Bough (1890) exemplified early anthropological thought, which was steeped in evolutionary theories. Frazer and his contemporaries, such as E.B. Tylor, posited that societies progressed through stages from “savagery” to “civilization.” This evolutionary perspective justified colonial domination by portraying European societies as more advanced and non-European cultures as primitive and in need of guidance.

While Frazer himself did not engage directly in colonial administration, his work influenced colonial attitudes by reinforcing hierarchical views of cultures. Colonial officials used such theories to legitimize their rule, arguing that they were bringing progress to “backward” societies.

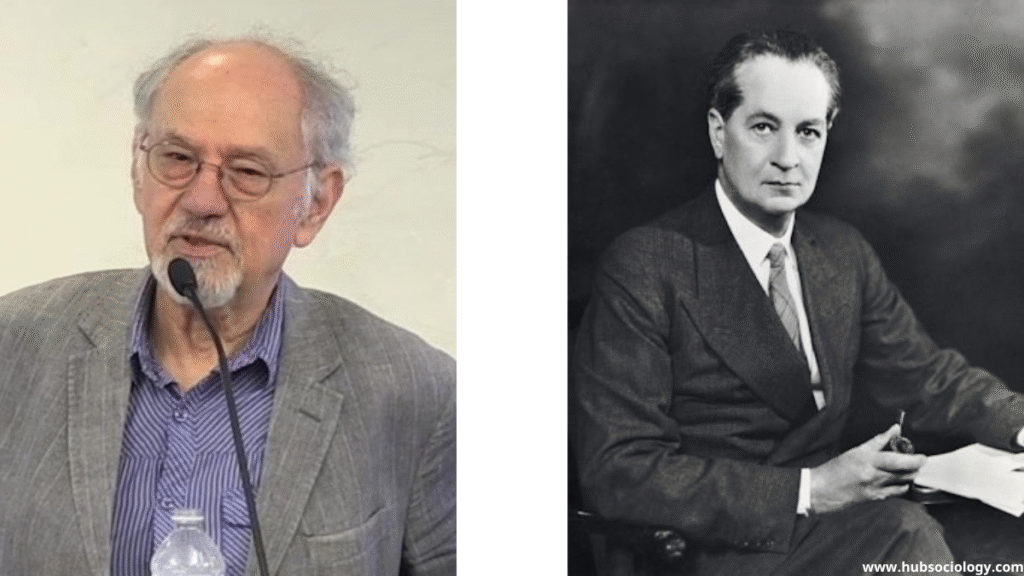

2. Bronisław Malinowski and Functionalist Fieldwork

A turning point in British anthropology came with Bronisław Malinowski, who pioneered participant observation during his fieldwork in the Trobriand Islands (1915-1918). Malinowski’s Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1922) established ethnographic fieldwork as a cornerstone of anthropological research.

Malinowski’s functionalist approach viewed societies as integrated systems where each institution (kinship, religion, economy) served a purpose in maintaining social order. While his methodology was groundbreaking, his work was also shaped by colonial contexts. He conducted research under British colonial rule and acknowledged the impact of colonialism on indigenous societies, though his primary focus was on documenting pre-colonial structures.

3. A.R. Radcliffe-Brown and Structural Functionalism

A.R. Radcliffe-Brown further developed structural functionalism, emphasizing the interconnectedness of social institutions. His studies in the Andaman Islands and Africa were influential in shaping British social anthropology. Like Malinowski, Radcliffe-Brown’s work was embedded in colonial settings, and his theories were sometimes used to justify indirect rule—a colonial policy where local leaders were co-opted to maintain control under British oversight.

Institutionalization of Anthropology in England

The institutional growth of anthropology in England was closely tied to colonial interests. Key developments included:

- Academic Departments: The London School of Economics (LSE) and Oxford University became centers for anthropological training. Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown held influential positions, training future anthropologists who often worked in colonial territories.

- Funding and Patronage: Research was frequently funded by colonial governments or institutions like the International African Institute, which sought anthropological insights to aid colonial governance.

- Museums and Ethnographic Collections: British museums, such as the Pitt Rivers Museum, amassed artifacts from colonized regions, reinforcing anthropological interest in non-European cultures.

Critiques of Anthropology’s Colonial Legacy

By the mid-20th century, as decolonization movements gained momentum, anthropology faced increasing scrutiny for its role in colonialism. Critics, including postcolonial scholars and anthropologists from the Global South, highlighted several issues:

- Complicity in Colonial Domination: Anthropology provided knowledge that facilitated colonial control. Ethnographic data was often used to manipulate indigenous governance systems, land ownership, and labor policies.

- Eurocentrism and Bias: Early anthropological theories were rooted in Eurocentric assumptions, portraying non-Western societies as static and inferior. This reinforced colonial ideologies of racial and cultural superiority.

- Ethical Concerns: Fieldwork conducted under colonial rule raised ethical questions about consent, representation, and the power dynamics between anthropologists and their subjects.

Postcolonial Transformations in Anthropology

The decline of colonialism and the rise of postcolonial criticism led to significant shifts in anthropological theory and practice:

- Reflexivity and Critique: Anthropologists like Talal Asad (Anthropology and the Colonial Encounter, 1973) called for a critical reassessment of the discipline’s history. Scholars began acknowledging anthropology’s colonial entanglements and striving for more ethical research practices.

- Decolonizing Anthropology: Efforts emerged to decolonize the discipline by amplifying indigenous voices, challenging Western theoretical dominance, and rethinking ethnographic methodologies.

- Applied and Advocacy Anthropology: Many anthropologists shifted towards advocacy, working with marginalized communities to address inequalities rather than serving colonial or state interests.

Conclusion on Social Anthropology

The emergence of social anthropology in England was inextricably linked to the British colonial project. Colonialism created both the demand for anthropological knowledge and the conditions under which early anthropologists conducted their research. While figures like Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown advanced methodological rigor, their work was embedded in colonial structures that shaped their interpretations of non-Western societies.

In the postcolonial era, anthropology has undergone critical self-reflection, grappling with its colonial past and striving to redefine itself as a more equitable and socially conscious discipline. Understanding this historical trajectory is essential for sociologists and anthropologists today, as it underscores the importance of ethical research, decolonial perspectives, and the ongoing need to challenge power imbalances in knowledge production.

Topic Related Questions on Social Anthropology

5-Mark Questions on Social Anthropology (Short Answer)

- Define social anthropology and explain its connection to colonialism.

- How did British colonial rule influence the development of social anthropology in England?

- Name two early British anthropologists and their contributions to the field.

- What was the significance of Bronisław Malinowski’s fieldwork in the Trobriand Islands?

- How did evolutionary theories in early anthropology justify colonialism?

- What is functionalism in anthropology, and how did it relate to colonial administration?

- Why were ethnographic studies important for colonial governance?

- What role did institutions like the London School of Economics (LSE) play in the growth of British anthropology?

- Briefly explain Talal Asad’s critique of anthropology’s colonial legacy.

- How did postcolonial scholars challenge traditional anthropological methods?

10-Mark Questions on Social Anthropology (Detailed Answer)

- Discuss the role of colonialism in shaping the early methodologies of British social anthropology.

- Compare the approaches of James Frazer and Bronisław Malinowski in studying non-Western societies.

- How did A.R. Radcliffe-Brown’s structural functionalism serve colonial interests?

- Examine the ethical concerns surrounding anthropological research during the colonial period.

- Analyze the impact of British colonial policies (e.g., indirect rule) on anthropological studies.

- Why did British anthropology shift from armchair theorizing to fieldwork in the early 20th century?

- Discuss the contributions of the International African Institute to colonial-era anthropology.

- How did museums like the Pitt Rivers Museum contribute to anthropological knowledge under colonialism?

- Explain the concept of “decolonizing anthropology” and its significance today.

- What were the major criticisms of anthropology after the decline of colonialism?

15-Mark Questions on Social Anthropology (Essay-Type)

- “Social anthropology in England was a product of colonialism.” Critically evaluate this statement.

- Discuss how early British anthropologists contributed to both the understanding and misrepresentation of colonized societies.

- Examine the transition from evolutionary anthropology to functionalism in the context of British colonialism.

- How did the institutionalization of anthropology in England reflect colonial interests?

- “Anthropology was both a tool and a critique of colonialism.” Analyze this statement with examples.

- Evaluate the role of ethnographic fieldwork in reinforcing or challenging colonial power structures.

- Discuss the postcolonial critiques of anthropology and their impact on contemporary anthropological practices.

- Compare the colonial influences on British anthropology with anthropological developments in other European colonial powers (e.g., France, Germany).

- How did indigenous resistance and decolonization movements reshape anthropological theories?

- Assess the relevance of early British social anthropology in today’s globalized and postcolonial world.

1 thought on “Colonialism and the Emergence of Social Anthropology in England: A Sociological Perspective”