Introduction on Weber’s Protestant Ethic

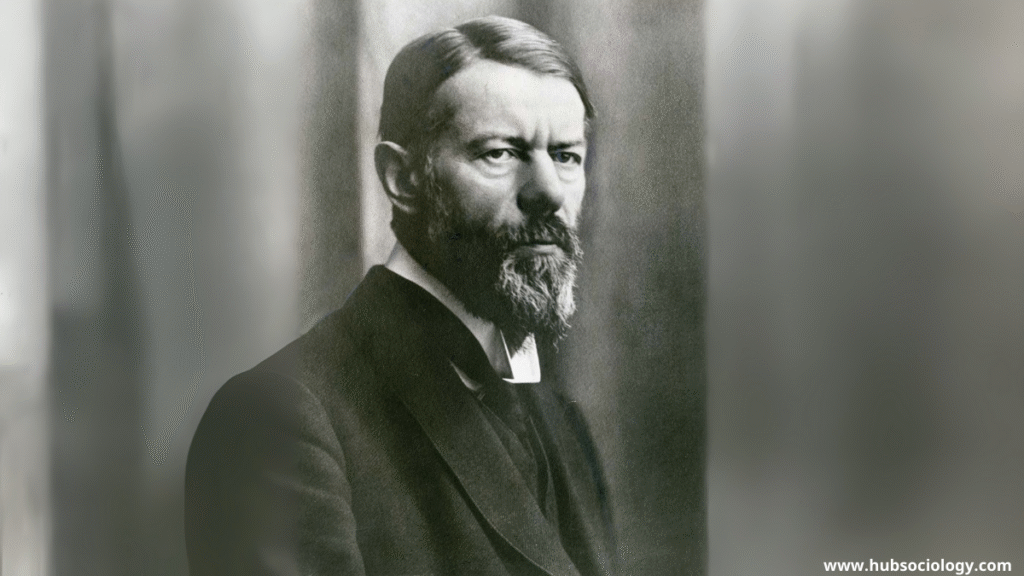

Max Weber, one of the founding figures of sociology, profoundly shaped our understanding of the relationship between culture, economy, and religion. In his classic work “The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism” (1905), Weber explored how religious values—specifically those derived from Protestantism—played a critical role in shaping the moral foundation of modern capitalism. He argued that Protestant beliefs, particularly Calvinist notions of calling, predestination, and disciplined labor, gave rise to a distinctive “spirit” that supported rational economic behavior, thrift, and productivity.

But more than a century later, in a globalized and secular age, the question arises: Does capitalism still need religion? Can the economic system that once drew moral energy from faith continue to thrive without it? In exploring this, we must understand Weber’s theory, its historical context, and the transformations of capitalism in the modern world.

Table of Contents

Weber’s Theory: The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism

Weber’s argument begins with a simple sociological observation: capitalism did not emerge everywhere in the same form. While markets, trade, and moneylending existed in many ancient civilizations—such as in China, India, and the Middle East—the particular spirit of modern capitalism appeared first in Western Europe, especially among Protestant communities. Weber sought to understand why.

1. The Religious Roots of Economic Rationality

According to Weber, the Protestant Reformation, especially the teachings of Martin Luther and John Calvin, transformed people’s understanding of work, morality, and salvation. Luther’s idea of Beruf (calling) redefined ordinary labor as a form of divine service. Every occupation, from farming to accounting, could be seen as fulfilling God’s will. Work was not merely a means to survive—it became a moral duty.

Calvinism, with its doctrine of predestination, added a psychological twist. Since one’s salvation was predetermined by God, believers could not earn it through good deeds. Yet, the faithful sought signs of being among the elect. Hard work, discipline, and economic success became evidence of divine favor. Thus, material success was not pursued for pleasure but as proof of moral worth and spiritual election.

2. The Rise of the “Spirit of Capitalism”

From this religious foundation emerged what Weber called the spirit of capitalism—a cultural ethos characterized by:

- Rational organization of work and time

- Discipline, frugality, and avoidance of waste

- Reinvestment of profits instead of indulgent consumption

- A belief that economic success reflects moral responsibility

This “spirit” differed from mere greed or materialism. Traditional societies valued consumption, leisure, and communal exchange, whereas modern capitalism prized rational profit-making and continuous reinvestment. For Weber, this rational, disciplined orientation was not natural—it was culturally produced through religious ethics.

3. The Irony of Secularization

Weber noted an irony: while Protestantism helped give birth to capitalism, the success of capitalism eventually undermined the religious basis that created it. Once rational economic behavior became institutionalized through bureaucracy, law, and education, it no longer required religious motivation. Modern individuals, he warned, might become trapped in an “iron cage” of rationality—working not for salvation or moral meaning, but out of compulsion, habit, and market necessity.

The Sociological Meaning of Weber’s Argument

Weber’s analysis goes far beyond religion or economics. It is a sociological study of how ideas shape social institutions and how moral values influence economic structures. His theory connects culture, belief, and social behavior—revealing how the subjective world of values can transform the objective world of markets.

Three key sociological implications emerge:

- Cultural Determinism of Economic Behavior

Economic systems are not only determined by material conditions but also by cultural and moral orientations. The capitalist “spirit” is a social construct shaped by values. - Rationalization of Modern Life

Weber’s broader theory of rationalization—where all spheres of life (law, education, administration) become governed by efficiency and calculation—originates in this religious-to-secular transformation. - The Tension Between Meaning and Modernity

Capitalism, once infused with moral meaning, now functions autonomously. This creates a world that is efficient but often spiritually empty—what Weber saw as the “disenchantment of the world.”

From Faith to Function: The Secularization of Capitalism

Weber’s insights continue to resonate in the 21st century, but the link between religion and capitalism has transformed dramatically. Modern capitalism no longer depends directly on Protestant ethics, yet its values still echo the same discipline and rationality.

1. The Decline of Religious Motivation

Contemporary capitalist societies are largely secular. Work, profit, and consumption are guided not by divine duty but by market incentives, technological innovation, and corporate culture. The ethic of hard work persists, but its meaning has shifted:

- Success is a personal achievement, not divine approval.

- Work is a path to self-fulfillment, not salvation.

- Discipline is enforced by competition, not conscience.

The moral energy once derived from religion has been replaced by economic necessity and cultural individualism.

2. The Rise of Consumer Capitalism

If early capitalism emphasized saving and reinvestment, late modern capitalism glorifies consumption and pleasure. Advertising, media, and global marketing encourage spending rather than restraint. This marks a reversal of the original Protestant ethic, which condemned luxury as sinful. Today, consumerism functions as a secular religion—offering identity, meaning, and belonging through brands and lifestyle choices.

3. Capitalism as a Self-Sustaining System

Weber foresaw this shift. In modern bureaucratic capitalism, rational calculation replaces religious faith as the guiding principle. The system now operates autonomously through laws of supply and demand, technological progress, and global networks. Capitalism, in effect, has secularized itself—it no longer needs religion to function.

Does Capitalism Still Need Religion?

To answer this question, we must distinguish between economic functioning and moral legitimacy. Capitalism can operate efficiently without religion, but can it sustain moral meaning without it?

1. Capitalism Without Religion: Functional Success

From a structural-functional perspective, capitalism has adapted to secular rationality. Corporate management, digital innovation, and financial markets function according to logic, data, and efficiency. The Protestant virtues of punctuality, discipline, and diligence are now institutionalized in organizational culture, education, and technology. Multinational corporations enforce work ethics through policies, not sermons.

Thus, capitalism no longer needs religion for motivation—it reproduces its own discipline through economic systems and social expectations. Weber’s prophecy of the “iron cage” is fulfilled: work is rationalized and detached from spiritual meaning.

2. The Moral Crisis of Modern Capitalism

However, from a sociological and ethical standpoint, the absence of religion has created a moral vacuum. Capitalism today faces crises of inequality, exploitation, environmental degradation, and alienation. The market’s pursuit of profit often lacks moral restraint. In this sense, Weber’s concern about “disenchantment” becomes highly relevant.

Without a unifying moral framework—religious or otherwise—capitalism risks becoming an amoral system driven by short-term gain. Sociologist Jürgen Habermas argues that modern societies still depend on “moral resources” inherited from religion, even if they have become secularized. The sense of duty, fairness, and social responsibility cannot be sustained by economics alone.

3. The Return of Spirituality in a Secular World

Interestingly, while traditional religion has declined in the West, new forms of spirituality have emerged—such as mindfulness, ethical consumerism, and sustainability movements. These can be seen as secular substitutes for the moral and spiritual discipline once provided by religion. They attempt to restore meaning and ethical direction to economic life.

For example:

- “Green capitalism” combines profit with environmental ethics.

- Corporate social responsibility (CSR) reintroduces moral accountability.

- The “purpose-driven business” reflects a quasi-religious ideal of moral capitalism.

Thus, while capitalism may not need institutional religion, it still seeks moral legitimacy—whether through ethics, spirituality, or humanitarian values.

Global Perspectives: Beyond Protestantism

Weber’s thesis was grounded in Western Christianity, but in the 21st century, capitalism is global, thriving in diverse cultural contexts—Japan, China, India, and the Islamic world. This raises the question: can non-Protestant societies generate similar capitalist ethics?

1. Confucian Capitalism in East Asia

In Japan, South Korea, and China, Confucian values of discipline, education, and family duty have provided moral foundations for economic success. Sociologists describe this as “Confucian capitalism”—a system where collective harmony and social obligation coexist with market rationality. This challenges Weber’s claim that Protestantism was uniquely suited to capitalism.

2. Islamic and Hindu Business Ethics

Islamic finance, based on principles of fairness and prohibition of interest (riba), offers an alternative moral economy. Similarly, Hindu notions of karma yoga (duty-bound work) and dharma (righteous conduct) shape business practices in India. These examples show that capitalism can adapt to multiple ethical systems, religious or secular.

3. Globalization and Cultural Hybridization

In today’s interconnected world, capitalism blends diverse cultural values. It no longer depends on a single religious ethos but thrives on flexible, hybrid moralities. Yet the Weberian insight remains: economic systems always require some form of moral legitimacy, whether religious, cultural, or ethical.

Weber’s Relevance in the 21st Century

Weber’s analysis continues to inform contemporary sociology for several reasons:

- It connects culture and economy, showing that material systems depend on moral ideas.

- It anticipates the secularization of modern life, where rationality replaces faith but leaves an existential void.

- It invites moral reflection, reminding us that economic progress without ethical grounding risks dehumanization.

Today’s capitalism, marked by digital labor, automation, and global inequality, faces the same moral question Weber asked: What gives work its meaning? When humans become cogs in a global machine, the search for purpose—once answered by religion—returns as a sociological and psychological necessity.

Conclusion on Weber’s Protestant Ethic

Max Weber’s Protestant Ethic remains one of sociology’s most profound explorations of how ideas shape society. His thesis—that Protestant religious values fostered the disciplined, rational behavior necessary for capitalism—offers not only historical insight but also a moral lens for evaluating modern life.

In the 21st century, capitalism no longer depends on religion for its functioning. It is self-sustaining, global, and largely secular. Yet Weber’s warning about the “iron cage” has come true: economic rationality has replaced moral meaning, leaving individuals searching for purpose amid material abundance.

So, does capitalism still need religion?

Not for its survival—but perhaps for its soul. Without moral guidance, capitalism risks losing its human essence. Whether through religion, ethics, or new forms of spirituality, societies must rediscover the values that make economic progress serve human well-being rather than enslave it. Weber’s work reminds us that while systems may change, the quest for meaning remains eternal.

Do you like this this Article ? You Can follow as on :-

Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/hubsociology

Whatsapp Channel – https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029Vb6D8vGKWEKpJpu5QP0O

Gmail – hubsociology@gmail.com

Topic-Related Questions on Weber’s Protestant Ethic

5 Marks on Weber’s Protestant Ethic

- What does Max Weber mean by the “Protestant Ethic”?

- Explain the relationship between religion and capitalism in Weber’s theory.

- What is meant by the “spirit of capitalism”?

10 Marks on Weber’s Protestant Ethic

- Discuss Weber’s thesis on the Protestant Ethic and its role in the development of capitalism.

- Explain how secularization transformed the religious basis of modern capitalism.

- Critically analyze whether capitalism can function without religion in today’s world.

15 Marks on Weber’s Protestant Ethic

- Examine Weber’s argument in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism and evaluate its relevance to contemporary capitalist societies.

- “Capitalism no longer needs religion, but still seeks moral legitimacy.” Discuss with sociological arguments.

- Compare Weber’s analysis of Protestant ethics with non-Western forms of capitalist ethics (e.g., Confucian or Islamic capitalism).