Introduction

Japan stands as one of the most advanced societies in the world—technologically, economically, and demographically unique. Among its defining social challenges is the phenomenon of rapid population aging. With nearly 30% of its citizens aged 65 and above, Japan has become the world’s oldest nation by proportion of elderly. This demographic transformation—known as kōreika shakai (aging society)—is reshaping the country’s social structure, economy, family relations, and welfare system. From a sociological perspective, the aging of Japan’s population reveals deeper insights into modernity, social change, and the restructuring of intergenerational relations.

This article examines Japan’s aging society in sociological terms—tracing its causes, impacts, and adaptive responses. It draws upon theories of modernization, structural functionalism, symbolic interactionism, and social policy perspectives to understand how Japanese society is coping with longevity and demographic imbalance.

1. Demographic Overview: The Rise of the Aging Society

Japan’s aging trend began after World War II, when improvements in healthcare, sanitation, and nutrition significantly reduced mortality rates while fertility rates fell sharply. According to the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, by 2025, one in every three Japanese citizens will be 65 or older. Life expectancy in Japan now exceeds 84 years, among the highest globally, while the total fertility rate stands at around 1.3—well below the replacement level of 2.1.

The aging process in Japan can be divided into three distinct phases:

- Post-war modernization (1950–1970): Rapid urbanization and industrialization led to smaller family sizes and migration from rural to urban centers.

- Economic boom and stabilization (1970–1990): The traditional family structure—where multiple generations lived together—began to erode as nuclear families became dominant.

- Contemporary period (1990–present): With low fertility and extended longevity, Japan entered a “super-aged society,” where the elderly outnumber the young by a large margin.

From a sociological standpoint, this demographic reality reflects the transformation of social institutions—particularly family, work, and welfare—under the forces of modernization and individualism.

2. Sociological Theories and Aging

Understanding Japan’s aging society requires applying sociological theories that explain how societies adapt to demographic changes.

a. Modernization Theory

Modernization theory posits that as societies industrialize, the status of older people tends to decline. In traditional agrarian societies, elders were respected as holders of wisdom and property, but in modern capitalist economies, value shifts toward productivity and innovation. In Japan, this pattern is evident: industrialization reduced the role of elderly people in family decision-making and economic contribution. Elders became dependent on pensions rather than being central to production, leading to a gradual loss of status and authority.

b. Structural Functionalism

From the structural functionalist viewpoint, every part of society functions to maintain stability. The aging population disrupts this equilibrium by creating a dependency ratio where fewer working-age individuals support more retirees. The state and institutions must adapt by reforming pension systems, healthcare, and employment policies to sustain societal balance. Thus, aging becomes a structural issue, requiring functional adjustments through policies like “active aging” and senior employment programs.

c. Symbolic Interactionism

This micro-level perspective focuses on how aging is socially constructed. In Japan, old age is often linked to the concept of ikigai—a sense of purpose or reason for being. While traditional cultural values such as oyakōkō (filial piety) and respect for elders remain strong, social attitudes are changing. Many elderly individuals redefine aging as an opportunity for self-realization, volunteering, or lifelong learning. Hence, aging in Japan is not merely biological but also symbolic—reflecting changing meanings of dignity, work, and contribution.

d. Conflict Theory

Conflict theorists emphasize inequality in resource distribution between generations. In Japan, young people face economic burdens from taxation and social insurance to support the elderly population. This “intergenerational contract” has become a source of tension. Elderly citizens, in turn, face economic disparities—those with corporate pensions live comfortably, while others, particularly women and rural residents, struggle financially. Aging thus reflects broader issues of class and inequality within Japanese society.

3. Social Consequences of Aging in Japan

a. Family and Community Transformation

Traditionally, Japanese families followed a stem family system (ie system), where multiple generations lived together and the eldest son cared for his parents. However, urbanization, increased mobility, and women’s participation in the workforce have weakened this model. More elderly people now live alone or in couples without children. According to statistics, nearly 7 million elderly Japanese live alone—a phenomenon known as kodokushi or “lonely death,” where individuals die without family contact and remain undiscovered for days or weeks.

This trend symbolizes the fragmentation of social ties and decline of traditional community networks. Sociologists view it as a symptom of individualization and the weakening of collective support structures.

b. Economic and Labor Implications

Japan’s shrinking workforce poses challenges for economic productivity and welfare sustainability. With fewer young workers contributing to taxes, the social security system faces immense pressure. The government has responded by encouraging the elderly to remain in the workforce longer—policies promoting “re-employment after retirement” and “silver human resource centers” enable seniors to engage in part-time or community work.

From a sociological angle, this extension of working life redefines retirement and challenges conventional notions of age-based roles. Work becomes not just economic necessity but also a means of identity and social participation.

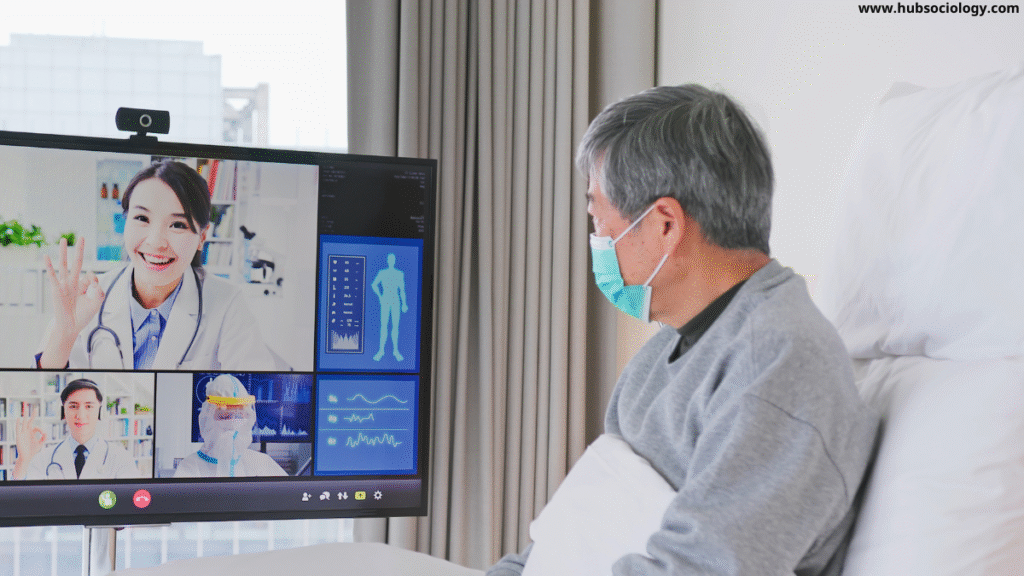

c. Healthcare and Social Welfare

Japan’s universal health insurance system and long-term care insurance (LTCI, established in 2000) represent institutional adaptations to population aging. However, these systems face sustainability challenges due to rising medical costs. Sociologically, the healthcare model reflects a shift from family-based caregiving to state-supported care—illustrating the transition from informal to formal welfare systems.

This also raises moral and ethical questions: To what extent should the state replace family responsibility? How do social norms adjust to institutional care for the elderly? Such questions reflect tensions between traditional values and modern welfare structures.

d. Rural Aging and Depopulation

In rural Japan, aging is particularly severe. Young people migrate to cities, leaving behind elderly residents. Entire villages face depopulation, becoming “ghost villages” (genkai shūraku). From a sociological viewpoint, this represents spatial inequality—uneven development between urban and rural regions. The loss of social institutions like schools and markets further isolates rural elders, reinforcing a cycle of decline.

Community sociology highlights how these regions attempt to adapt through local initiatives—senior cooperatives, volunteer networks, and community-based farming—but their survival remains uncertain without broader state intervention.

4. Gender and Aging

Gender plays a crucial role in Japan’s aging experience. Women constitute the majority of the elderly population due to longer life expectancy. Yet, many older women face financial insecurity because they often worked part-time or as homemakers, leading to lower pensions. This feminization of aging reflects persistent gender inequalities in the labor market and welfare system.

Moreover, women traditionally act as caregivers for both children and elderly parents. The sandwich generation—middle-aged women caring for both aging parents and grown children—faces intense emotional and physical stress. From a feminist sociological lens, Japan’s aging society exposes the gendered nature of unpaid labor and the unequal distribution of caregiving responsibilities.

5. Cultural Dimensions of Aging

Despite structural challenges, Japanese culture retains deep respect for the elderly. The annual Respect for the Aged Day (Keirō no Hi) and intergenerational community events symbolize moral appreciation for senior citizens. Concepts like wa (harmony) and giri (duty) encourage social cohesion even in an aging context.

At the same time, media representations of aging are shifting—from depicting elderly people as dependents to portraying them as active, wise, and resourceful individuals. The rise of senior idols, elderly entrepreneurs, and “active aging” movements illustrate new cultural narratives that empower rather than marginalize old age.

Symbolic interactionists see this as evidence that age is a flexible social identity—constructed and reconstructed through interaction and cultural discourse.

6. State and Policy Responses

Japan has developed multifaceted policies to address its aging society. Sociologically, these policies reflect a balance between welfare capitalism and familialism.

- Long-Term Care Insurance (LTCI): Established in 2000, it allows citizens to access care services based on need, not family income, thereby socializing care responsibilities.

- Community-based Integrated Care Systems: These initiatives promote local networks that combine medical, social, and volunteer support.

- Employment for the Elderly: Policies encouraging continued work after 65 aim to reduce dependency and maintain intergenerational balance.

- Technological Innovations: Japan leads in using robotics and AI for elderly care—examples include robotic caregivers, smart homes, and monitoring systems, illustrating the fusion of technology and sociology.

From a sociological perspective, these adaptations show institutional resilience and innovation within an aging social structure.

7. Intergenerational Relations and Social Cohesion

One major sociological concern is maintaining intergenerational solidarity. As economic and social gaps widen between young and old, potential conflicts arise over welfare spending, employment opportunities, and taxation. The “silver democracy” phenomenon—where the elderly dominate the electorate—raises questions about political representation and fairness toward younger generations.

However, initiatives like intergenerational housing, shared learning centers, and volunteer programs aim to rebuild connections. Sociologists interpret these as mechanisms of social integration, where mutual understanding and shared spaces can strengthen social cohesion.

8. Comparative and Global Implications

Japan serves as a global case study in demographic transition. Other nations—especially South Korea, China, Germany, and Italy—are now following similar paths. Japan’s sociological experience demonstrates that aging is not merely a demographic issue but a transformation in the meaning of work, family, and social responsibility.

Sociologists studying Japan’s case highlight three lessons:

- Modernization without demographic sustainability leads to imbalance.

- Cultural values can both hinder and help adaptation.

- Social innovation is essential for creating inclusive, age-friendly societies.

9. Future Directions and Challenges

The sociological future of Japan’s aging society depends on several intersecting factors:

- Reforming family structures to accommodate non-traditional caregiving models.

- Encouraging immigration to offset labor shortages, while addressing cultural integration challenges.

- Promoting gender equality to ensure balanced caregiving and pension security.

- Expanding community care models to prevent isolation and kodokushi.

- Redefining aging as an active and valuable life stage, not merely dependency.

Sociologists emphasize that sustainable aging requires a cultural shift—from viewing the elderly as a burden to recognizing them as contributors to social capital and community life.

Conclusion

Japan’s aging society offers profound sociological insights into the consequences of modernity, demographic transition, and cultural adaptation. The phenomenon of kōreika shakai is not simply about numbers—it represents a transformation in values, social structures, and collective consciousness. Through the lenses of various sociological theories, we see how Japan’s response blends tradition and innovation: preserving respect for elders while reimagining their role in a modern, dynamic society.

As the world moves toward similar demographic realities, Japan stands as both a warning and a model—showing that the aging of a nation can, with social creativity and cultural strength, become a story of resilience and renewal rather than decline.

Do you like this this Article ? You Can follow as on :-

Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/hubsociology

Whatsapp Channel – https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029Vb6D8vGKWEKpJpu5QP0O

Gmail – hubsociology@gmail.com

Topic-related Sociology Questions

5 Marks Questions (Short Answer Type)

- Define the term Aging Society in sociological context.

- What are the main demographic characteristics of Japan’s Aging Society?

- Mention two major causes of the Aging Society in Japan.

- What is meant by kōreika shakai in relation to Japan’s Aging Society?

- Explain the concept of ikigai and its role in understanding Japan’s Aging Society.

- What is kodokushi and why is it a social concern in an Aging Society?

- List two sociological theories that help explain the emergence of an Aging Society.

10 Marks Questions (Medium Answer Type)

- Discuss how Modernization Theory explains the emergence of an Aging Society in Japan.

- Examine the impact of Japan’s Aging Society on traditional family structures and intergenerational relations.

- How does gender inequality manifest within Japan’s Aging Society?

- Describe the role of government policies in addressing challenges related to an Aging Society.

- Explain the economic and labor market implications of Japan’s Aging Society.

- How has technology been used to address social problems in Japan’s Aging Society?

- Discuss the cultural meanings of aging and their influence on the Aging Society in Japan.

15 Marks Questions (Long Answer / Essay Type)

- Critically analyze the social, economic, and cultural consequences of an Aging Society with special reference to Japan.

- Evaluate the applicability of sociological theories—Modernization, Functionalism, and Symbolic Interactionism—in understanding Japan’s Aging Society.

- Discuss the transformation of intergenerational relations and family structures in Japan’s Aging Society.

- Assess the effectiveness of Japan’s state policies and welfare programs in managing the Aging Society.

- Compare Japan’s Aging Society with that of another industrialized nation, highlighting similarities and sociological differences.

- Examine the role of social institutions (family, economy, and state) in adapting to the Aging Society in Japan.

- “Japan’s Aging Society is both a challenge and an opportunity for social innovation.” — Discuss this statement with sociological reasoning.