Introduction

Nation-building and the construction of national identity are deeply sociological processes, shaped not only by political leadership and statecraft but also by historical memory, cultural narratives, ethnic composition, and global influences. In Kazakhstan, a vast Central Asian country with a complex past, these processes take on special significance. Since gaining independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Kazakhstan has faced the dual challenge of consolidating a sovereign state and forging a cohesive national identity in the context of multiethnic diversity, global economic integration, and shifting geopolitical realities.

The sociological study of Kazakhstan’s nation-building sheds light on broader questions about how post-Soviet societies negotiate history, ethnicity, language, religion, and modernization. It also illustrates the ways in which state policies and social processes intersect to shape collective belonging and national consciousness.

Table of Contents

Historical Context: From Soviet Legacy to Independence

The legacy of Soviet rule profoundly shaped Kazakhstan’s social structure and identity formation. The USSR promoted a supranational “Soviet identity” while simultaneously managing ethnic categories through census classifications and regional policies. In Kazakhstan, this left a dual legacy: on one hand, Soviet-era modernization brought industrial development, urbanization, and literacy; on the other hand, it marginalized Kazakh language and culture while fostering Russification.

At the time of independence in 1991, ethnic Kazakhs constituted only about 40% of the population, while Russians and other minorities together made up the majority. This demographic reality meant that national identity could not be built purely on ethnic exclusivity. Instead, Kazakhstan’s leaders—especially its first president, Nursultan Nazarbayev—crafted a civic-nationalist framework that sought to balance ethnic Kazakh revival with inclusivity for minorities.

From a sociological perspective, the disintegration of the Soviet Union created a “cultural void” in Kazakhstan, requiring new symbolic anchors to unite people. Independence provided an opportunity to redefine historical narratives, revalorize traditions, and promote new social institutions that would legitimize the idea of “Kazakhstani” nationhood.

Theoretical Framework: Nation-Building and Identity in Sociology

Sociological theories help us understand Kazakhstan’s path:

- Benedict Anderson’s “Imagined Communities” highlights that nations are socially constructed through shared symbols, institutions, and narratives. Kazakhstan’s leaders have worked to build such an imagined community through language policy, historical reinterpretation, and cultural revival.

- Anthony D. Smith’s Ethno-symbolism stresses the role of myths, memories, and symbols in national identity. Kazakhstan’s revival of nomadic traditions, the celebration of historical figures like Abai, and the emphasis on Tengriist and Islamic cultural elements reflect ethno-symbolic strategies.

- Modernization Theory suggests that urbanization, industrialization, and education promote nation-building by creating shared experiences and institutions. Kazakhstan’s rapid modernization—particularly in cities like Almaty and Astana (Nur-Sultan)—has been tied to its nation-building agenda.

- Multiculturalism and Civic Nationalism: Sociologists note that multiethnic societies often balance between ethnic nationalism and civic nationalism. Kazakhstan embodies this tension, promoting the idea of a “Kazakh nation” while also fostering the inclusive “Kazakhstani” identity.

Key Dimensions of Nation-Building in Kazakhstan

1. Language Policy and Cultural Revival

Language is central to national identity. After independence, Kazakhstan declared Kazakh the state language while maintaining Russian as the language of interethnic communication. This bilingual policy reflects sociological pragmatism: Kazakh revival is tied to ethnic pride and cultural authenticity, while Russian ensures social stability and international connectivity.

Efforts to expand Kazakh usage include reforms in education, media, and public administration. The decision to transition from Cyrillic to Latin script is symbolic, representing both a cultural de-Sovietization and a reorientation towards global integration.

From a sociological angle, these policies generate both opportunities and tensions. For ethnic Kazakhs, they restore cultural dignity; for Russian-speaking minorities, they sometimes generate anxiety about marginalization. The balancing act illustrates the challenge of linguistic nation-building in a diverse society.

2. Historical Narratives and Collective Memory

Nation-building often relies on rewriting history to emphasize continuity and uniqueness. Kazakhstan has elevated pre-Soviet heritage, especially the nomadic past, as central to its identity. Celebrations of historical figures like Chinggis Khan (in broader Turkic context) and national poets like Abai Kunanbayev symbolize the valorization of indigenous roots.

At the same time, the memory of Soviet modernity—industrial development, education, and scientific progress—is not entirely erased. Instead, Kazakhstan presents itself as a bridge between its nomadic traditions and Soviet modernity, blending both narratives.

Sociologically, this illustrates cultural hybridity: Kazakhstan’s identity is not simply a return to the past but a creative synthesis that legitimizes present-day nationhood.

3. Ethnicity, Diversity, and Social Cohesion

Kazakhstan is home to more than 130 ethnic groups, including Kazakhs, Russians, Uzbeks, Ukrainians, Uyghurs, Germans, and Koreans. Managing this diversity is central to nation-building.

The Assembly of People of Kazakhstan (APK), established in 1995, is a unique sociopolitical institution designed to give minorities representation and promote interethnic harmony. It symbolizes the state’s commitment to civic nationalism, where belonging is defined not by ethnicity but by loyalty to the state.

However, sociologists note that ethnic hierarchies still persist: Kazakhs enjoy symbolic primacy as the titular nation, while minorities sometimes feel socially marginalized. This reflects a dual model of nationhood—ethnic Kazakh dominance coexisting with civic inclusivity.

4. Religion and Spiritual Identity

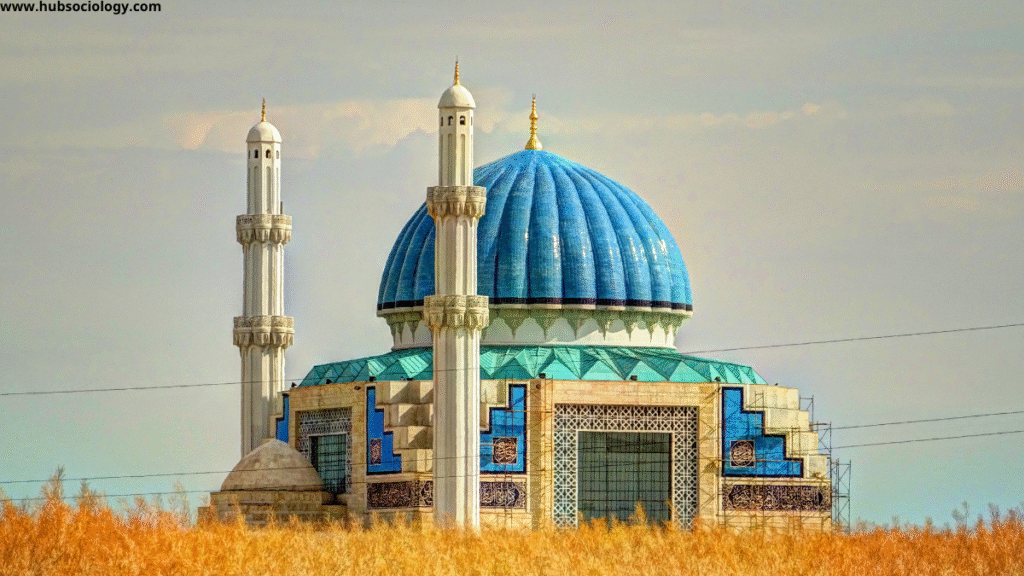

Although officially secular, Kazakhstan recognizes the sociological importance of religion in nation-building. Islam, particularly Hanafi Sunni Islam, is emphasized as part of Kazakh cultural identity, alongside traditional Tengriist elements.

Religious revival has been carefully managed by the state to prevent extremism while promoting cultural continuity. The restoration of mosques and inclusion of Islamic holidays reflect the integration of spirituality into national life.

Sociologically, religion serves as both a unifying force for ethnic Kazakhs and a marker of distinction from the secular Soviet past. However, with significant Christian and non-religious minorities, the state avoids excessive Islamization, again balancing ethnic and civic elements.

5. Urbanization, Modernization, and Globalization

The relocation of the capital from Almaty to Astana (now again Astana) in 1997 was more than political—it was a symbolic act of nation-building. The new capital embodies modernity, ambition, and independence, with futuristic architecture designed to project Kazakhstan’s global identity.

Urbanization has fostered new forms of social integration, with multiethnic populations interacting in shared educational, economic, and cultural spaces. Globalization, through oil wealth and international diplomacy, further positions Kazakhstan as a modern nation-state.

Yet modernization also creates sociological contradictions: rural Kazakhs may feel alienated from urban elites, and the pursuit of global recognition sometimes clashes with grassroots cultural identity.

Challenges in Nation-Building

Despite successes, Kazakhstan faces ongoing challenges:

- Ethnic Tensions: While official discourse promotes harmony, occasional local conflicts reveal underlying grievances.

- Language Divide: Many urban populations remain primarily Russian-speaking, complicating full Kazakhization.

- Generational Shifts: Younger Kazakhs increasingly embrace global identities alongside national pride, creating hybrid cultural forms.

- Authoritarian Legacy: Nation-building has often been top-down, with limited civic participation, raising questions about genuine identity formation.

- Geopolitical Pressure: Russia’s influence, especially after its invasion of Ukraine, complicates Kazakhstan’s balancing act between sovereignty and regional ties.

Nation-Building as an Ongoing Process

Sociologists emphasize that nation-building is not a one-time event but a continuous negotiation. In Kazakhstan, national identity remains fluid, shaped by global events, economic transformations, and internal dynamics. The current leadership continues to adapt symbols, policies, and narratives to maintain cohesion.

The shift from Nazarbayev’s personalized nation-building (where the “Leader of the Nation” himself was central to identity) to broader civic narratives under President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev illustrates this evolution. The emphasis is gradually moving towards institutionalized nationalism rather than charismatic authority.

Comparative Perspective: Kazakhstan and Other Post-Soviet States

Comparing Kazakhstan with other post-Soviet republics highlights its unique sociological trajectory. While countries like the Baltic states emphasized ethnic nationalism and others like Kyrgyzstan struggled with instability, Kazakhstan adopted a more balanced model—strong state control combined with ethnic inclusivity.

This model has provided relative stability but also reflects sociological tensions between ethnic primacy (Kazakh culture at the core) and civic inclusivity (multiethnic harmony). Its success or failure may influence other multiethnic societies navigating post-imperial nation-building.

Conclusion

Nation-building and national identity in Kazakhstan are deeply sociological processes that reveal the interplay of history, ethnicity, language, religion, and modernization. Since independence, Kazakhstan has pursued a hybrid model—reviving Kazakh culture while promoting civic inclusivity for minorities.

The sociological dimensions highlight both opportunities and contradictions: while new narratives and institutions foster unity, ethnic hierarchies, linguistic divides, and global influences complicate the process. Yet, Kazakhstan’s experience shows that national identity is not static but continuously negotiated, adapting to internal diversity and external pressures.

Ultimately, Kazakhstan’s nation-building reflects a broader sociological truth: nations are not merely political entities but lived social realities, constructed through shared memory, symbols, and everyday practices. The Kazakhstani case underscores the resilience of societies in creatively negotiating identity amidst complexity—an ongoing experiment in forging unity within diversity.

Do you like this this Article ? You Can follow as on :-

Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/hubsociology

Whatsapp Channel – https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029Vb6D8vGKWEKpJpu5QP0O

Gmail – hubsociology@gmail.com