Youth protest movements have emerged as one of the most defining socio-political phenomena in Hong Kong over the past decade. From the 2014 Umbrella Movement to the 2019 Anti-Extradition Bill protests, young people have consistently been at the forefront of collective action, mobilizing in large numbers and shaping global conversations about democracy, identity, and state-society relations. Understanding these movements requires a sociological lens that goes beyond media narratives, focusing instead on the underlying structural, cultural, and relational dynamics that influence youth activism.

This article explores the sociological foundations of these movements by examining their historical roots, socio-political contexts, identity formations, organizational frameworks, and the evolving strategies of resistance.

Historical Context and Emergence of Youth-Led Protests

The emergence of youth protest movements in Hong Kong is deeply connected to the region’s colonial legacy and its transition to Chinese sovereignty in 1997. Under British rule, political rights were limited, yet the city’s exposure to Western legal frameworks and civil liberties created a political culture that valued freedom of expression. The “One Country, Two Systems” arrangement institutionalized a semi-autonomous status, promising Hong Kong a high degree of self-governance until 2047.

However, over the years, residents—particularly young people—began to perceive a narrowing of these freedoms. The increasing influence of Beijing in local affairs generated widespread anxiety about the erosion of autonomy, cultural distinctiveness, and democratic aspirations. The introduction of national education reforms in 2012, perceived as attempts at ideological indoctrination, was one of the earliest catalysts that mobilized thousands of students. This movement, led by the group Scholarism, signaled the rise of a highly educated and politically conscious youth.

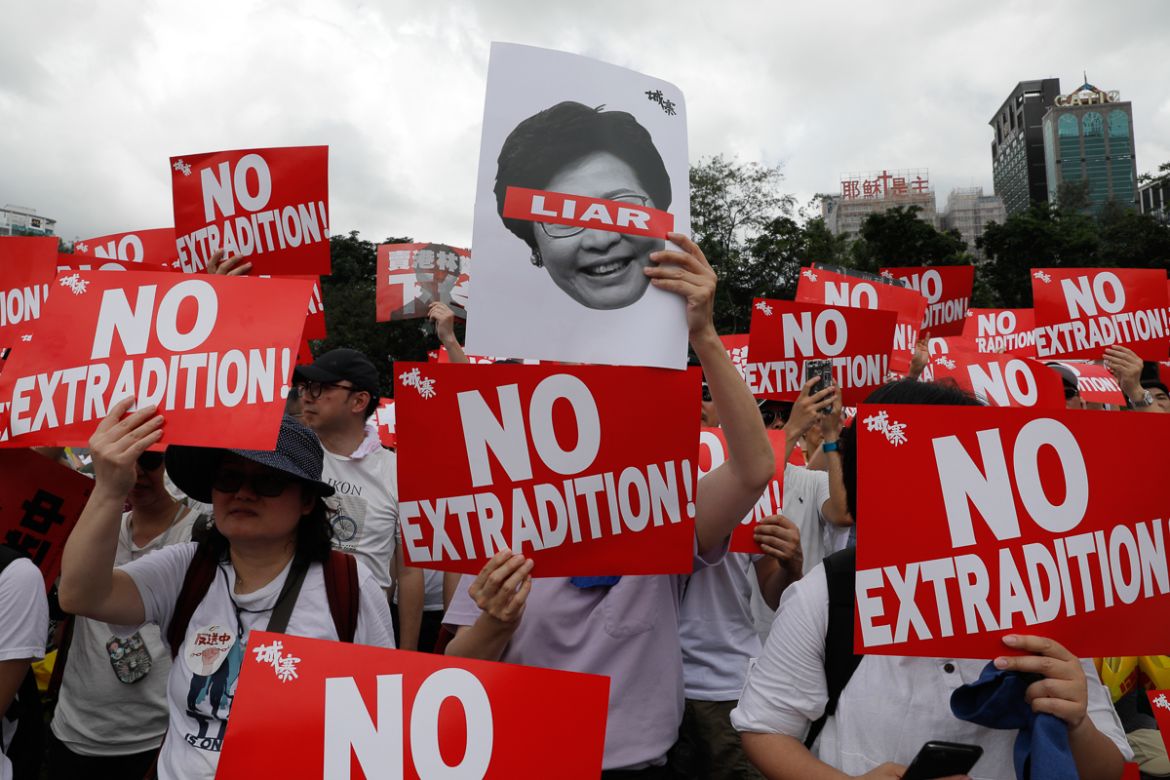

The 2014 Umbrella Movement further cemented the role of youth in political resistance. The movement was sparked by Beijing’s decision to restrict electoral reforms, leading to massive sit-ins and occupations. Young protesters used innovative tactics, mobile technology, and non-violent civil disobedience, highlighting a new generation’s political agency.

Socio-political Grievances and Theories of Relative Deprivation

A sociological understanding of youth activism in Hong Kong can be informed by the theory of relative deprivation, which explains collective action as a response to perceived injustices. Many young Hongkongers feel that their economic future has been compromised by structural inequalities, including rising housing prices, stagnant wages, and limited social mobility. The city’s neoliberal economic model has resulted in wealth concentration and reduced opportunities for middle-class advancement.

Even though Hong Kong is often described as a global financial centre, young people experience a strong sense of marginalization. They compare their social conditions not only to the older generation but also to their peers in other developed societies. This perceived gap fuels frustration, turning economic grievances into political discontent.

Youth protest movements also reflect anxieties surrounding identity and belonging. Many young Hongkongers identify less with mainland China than with a distinctly local identity shaped by Cantonese culture, civic participation, and international openness. Scholars argue that this identity conflict has produced what can be called “cultural relative deprivation,” in which youths fear the loss of their cultural and political autonomy.

Youth Identity, Political Socialization, and the Rise of New Localism

Identity construction plays a critical role in mobilizing youth participation in social movements. In the case of Hong Kong, the younger population grew up after the 1997 handover, during a time when debates about autonomy, political rights, and cultural distinctiveness intensified. Digital technology, global education, and exposure to international political norms influenced their worldview, making them more assertive in defending democratic values.

New localism—an ideological framework emphasizing Hong Kong identity and self-determination—became particularly influential. Unlike older generations who maintained pragmatic economic ties with mainland China, younger individuals often viewed integration policies with suspicion. The perceived threat to language, lifestyle, and political freedom strengthened localist sentiments and contributed to a more radical form of youth activism.

Political socialization also occurred through schools, universities, peer networks, and online communities. Students formed political groups, attended public forums, and consumed alternative media that challenged dominant state narratives. These processes not only politicized young people but also empowered them with organizational tools and symbolic resources.

Organizational Forms and Leaderless Resistance

One of the most distinctive features of Hong Kong’s youth protest movements is their innovative organizational style. While earlier movements such as the Umbrella Movement were led by recognizable student leaders, the 2019 Anti-Extradition Bill protests adopted a decentralized, leaderless structure. This shift occurred partly due to lessons learned from past mobilization efforts, where leaders were arrested or targeted, weakening the movement.

The slogan “Be Water,” inspired by Bruce Lee, symbolized the movement’s flexibility, spontaneity, and adaptability. Protest actions popped up across districts, making it difficult for authorities to predict and suppress mobilization. This horizontal form of organization reflects sociological theories of networked activism, where social ties, digital platforms, and community engagement replace traditional hierarchies.

Online forums such as LIHKG and messaging apps like Telegram became critical tools for coordination, deliberation, and strategy formation. These platforms enabled anonymous participation while allowing collective decisions to emerge from open discussions. The digital environment also facilitated the circulation of protest art, slogans, and emotional expressions, reinforcing solidarity and sustaining morale.

Cultural Forms of Resistance: Symbols, Art, and Collective Emotions

Culture plays an integral role in shaping the dynamics of social movements. Hong Kong’s youth protests developed a rich repertoire of cultural resistance, using artistic symbols and collective emotions to mobilize participants and attract global attention.

Protest art—posters, graffiti, Lennon Walls, and online illustrations—became a medium of counter-hegemonic expression. Symbols like the yellow umbrella, the black bloc attire, and the “Liberate Hong Kong” slogan communicated collective identity and defiance. Music, chants, and performance art helped forge emotional bonds and strengthen a sense of shared struggle.

Emotions like anger, hope, fear, and pride were collectively experienced and publicly expressed. In sociological terms, these emotional currents contributed to what Randall Collins calls “interaction ritual chains,” in which shared rituals elevate group solidarity and energize collective action. Hong Kong’s mass rallies, human chains, and memorial gatherings created powerful emotional atmospheres that reinforced the movement’s resilience.

The State, Policing, and Shifting Power Dynamics

State response is a crucial determinant of the trajectory of social movements. In Hong Kong, policing strategies evolved significantly from the largely restrained approach of earlier decades to more assertive and confrontational tactics, especially during and after the 2019 protests. Tear gas deployment, mass arrests, and the use of emergency powers signaled a shift in the state’s approach to dissent.

The introduction of the National Security Law (NSL) in 2020 marked a major turning point. The law criminalized secession, subversion, and collusion with foreign forces, creating an atmosphere of heavy surveillance and political risk. Many youth leaders were arrested, civil society groups disbanded, and protest-related activities curtailed.

From a sociological perspective, this represents the transformation of Hong Kong from a semi-autonomous liberal enclave to an increasingly authoritarian governance structure. The shift altered power relations between the state and civil society, limiting the spaces for political contestation.

Globalization, Transnational Solidarity, and Media Representation

Hong Kong’s youth protest movements are not isolated events but are embedded in global networks of communication, ideas, and political influence. International media extensively covered the protests, framing them as struggles for democracy against authoritarian pressure. This global attention inspired solidarity movements in other regions, linking Hong Kong to wider debates about human rights.

Transnational activism emerged through diasporic communities, who organized rallies, lobbied foreign governments, and amplified the voices of protesters abroad. Digital platforms enabled the global circulation of images, narratives, and political appeals, strengthening a sense of cross-border solidarity.

However, globalization also intensified geopolitical tensions. Beijing framed the protests as externally manipulated and accused foreign actors of fomenting unrest. This narrative influenced domestic perceptions and justified state intervention, illustrating how global-local interactions shape political meanings.

Youth Movements and the Reconfiguration of Hong Kong Society

The sociological impact of youth protest movements extends beyond street demonstrations. They have influenced public discourse, political culture, and generational relations in Hong Kong. Young people’s assertive participation challenged traditional norms of deference and political passivity, giving rise to a new political subjectivity grounded in activism and civic consciousness.

Family structures and intergenerational relations were also affected. Many older residents prioritized stability and economic concerns, while younger individuals emphasized values of justice and autonomy. This generational divide reflects broader cultural shifts and competing visions for Hong Kong’s future.

Furthermore, the protests led to the growth of alternative civil society forms—community mutual aid groups, student networks, political art collectives, and volunteer organizations. These groups continue to contribute to public life, even under tightened political controls.

Sociological Implications: Power, Identity, and Resistance

Youth protest movements in Hong Kong exemplify several key sociological concepts:

1. Power and Counterpower

The state’s assertion of authority through legal reforms and policing reflects centralized power, while decentralized youth movements represent counterpower via collective action. This dynamic illustrates Michel Foucault’s idea that power is dispersed and contested through everyday practices and resistance.

2. Identity Politics

The formation of a distinct Hong Kong identity—culturally, linguistically, and politically—shaped the motivations and ideologies of youth activism. Identity became both a mobilizing factor and a battleground contested by the state.

3. Social Movements and Collective Action

The use of digital networks, symbolic protest repertoires, and peer-driven coordination align with contemporary theories of social movements that emphasize horizontality, fluidity, and participatory action.

4. Structural Strain and Social Inequality

Economic insecurity, housing crises, and limited opportunities created structural strains contributing to youth disillusionment. These material factors intertwined with political grievances, demonstrating the complex relationships between inequality and dissent.

5. Cultural Resistance

Symbols, emotions, and collective rituals played powerful roles in sustaining movements. Cultural practices became forms of political expression and identity reinforcement.

Conclusion: The Future of Youth Activism in Hong Kong

The youth protest movements in Hong Kong represent a transformative chapter in the city’s sociopolitical landscape. Despite increased criminalization of dissent and shrinking civic spaces, the sociological forces that gave rise to these movements—identity conflicts, economic pressures, political disenfranchisement, and cultural autonomy—remain relevant. While traditional street protests have diminished due to the National Security Law, activism has shifted into new forms: digital expression, community initiatives, cultural production, and diasporic advocacy.

For sociologists, Hong Kong’s youth movements provide valuable insights into how contemporary societies navigate tensions between state power and civil liberties, global influences and local identities, and generational differences in aspirations and values. These movements underscore the enduring capacity of young people to shape political discourse, challenge authority, and envision alternative futures.

Hong Kong’s story is thus not only about protest but also about resilience, identity, and the sociological forces that drive youth to stand at the frontlines of social change.

FAQs on Youth Protest Movements in Hong Kong

1. What are the major youth protest movements in Hong Kong?

The most prominent youth-led movements include the 2012 Anti-National Education protests, the 2014 Umbrella Movement, and the 2019 Anti-Extradition Bill protests. These movements were sparked by political grievances related to autonomy, democratic rights, and perceived interference from mainland China.

2. Why are young people such a central force in Hong Kong’s protests?

Hong Kong youth are highly educated, digitally active, and sensitive to issues of identity, democracy, and future opportunities. Sociologically, they face economic pressure, limited housing mobility, and cultural tensions, which make them more likely to engage in activism.

3. What sociological factors influence youth participation in these movements?

Key factors include identity construction, relative deprivation, generational conflict, digital political socialization, economic insecurity, and the desire to protect civic freedoms. These elements collectively motivate young people to mobilize.

4. How does Hong Kong’s identity crisis contribute to youth activism?

Many young residents identify strongly as “Hongkongers” rather than “Chinese.” Perceived threats to language, autonomy, and cultural uniqueness intensify their desire to protect local identity, driving them into political action.

5. What role did digital technology play in youth protest movements?

Digital platforms such as Telegram, LIHKG, Instagram, and WhatsApp were crucial for leaderless coordination, rapid mobilization, sharing protest art, and spreading real-time information. Technology also ensured anonymity and reduced state surveillance risks.

6. What is the significance of the term “Be Water” in Hong Kong protests?

“Be Water” symbolizes flexible, decentralized, and rapid protest tactics inspired by Bruce Lee’s philosophy. It reflects how youths used fluid strategies to evade police control and adapt to changing conditions during demonstrations.

7. How did the state respond to youth-led movements?

The state employed a mix of policing measures, including tear gas, mass arrests, and later the National Security Law (NSL). The NSL criminalized forms of dissent, leading to reduced street mobilization and the arrest of many activists.

8. Do economic conditions contribute to youth protest participation?

Yes. Young people face high living costs, unaffordable housing, stagnant wages, and low upward mobility. These structural inequalities fuel feelings of frustration and relative deprivation, reinforcing political frustration.

9. How has international attention influenced the movement?

Global media coverage amplified the movement’s visibility, leading to international solidarity and diasporic activism. However, it also intensified geopolitical tensions, with Beijing accusing foreign forces of interference.

10. What is the future of youth activism under the National Security Law?

Traditional street protests have declined due to legal risks, but activism continues in new forms such as cultural production, digital expression, community mutual aid, academic advocacy, and activism among the Hong Kong diaspora.