China’s rapid economic transformation over the past four decades has reshaped global discussions on development, urbanization, and social change. Yet beneath the impressive growth lies a deeply rooted institutional mechanism that continues to shape life chances, identity, and social mobility for millions of Chinese citizens—the hukou system. Originally introduced in the 1950s as a household registration system, hukou still influences individuals’ access to education, healthcare, employment, and welfare, thereby producing and reproducing social inequalities. From a sociological perspective, the hukou system is more than an administrative tool; it is a form of social stratification embedded in state policy, shaping class formation and social exclusion in the world’s most populous country.

This article examines the hukou system through the lens of sociological theory, focusing on its origins, functions, and consequences for inequality. It also explores how hukou reforms are unfolding alongside China’s broader economic and political changes.

Table of Contents

1. Historical Origins and Sociological Foundations of Hukou

The hukou system (户口), formally established in 1958, was originally intended to control internal migration and support China’s planned economy. At its core, hukou categorizes every citizen into one of two statuses:

- Agricultural (rural) hukou

- Non-agricultural (urban) hukou

This distinction resembles a caste-like division that assigns different rights and responsibilities based on place of birth. Sociologically, hukou operates as:

A mechanism of social control

The early socialist state sought to prevent rural-urban migration to ensure food supply stability and maintain strict oversight of labour allocation. Hukou functioned as a surveillance tool, linking individuals to specific local authorities.

An institutionalized form of stratification

Much like feudal or caste systems, the hukou system ties social identity to birthplace. This creates ascribed status, determining life opportunities regardless of merit or mobility.

A tool for population management

By limiting urban migration, the government could provide welfare benefits to a smaller group of urban residents while relying on rural populations for agricultural labour.

This structure laid the foundation for long-term rural-urban inequalities that persist even within China’s modern capitalist economy.

2. Hukou as a System of Social Inequality

A. Inequality in Access to Public Goods

Urban hukou holders enjoy significantly better access to:

- Public education

- Healthcare services

- Pension and social insurance

- Subsidized housing

- Employment opportunities

Meanwhile, rural migrants working in cities—often referred to as the floating population—generally cannot access these services outside their registered areas.

According to sociological theories of structural inequality, institutions like hukou create “built-in” disadvantages, which accumulate across generations. A child born in a rural province is automatically assigned a lower-value hukou, shaping their educational pathway, healthcare access, and economic prospects.

B. Labour Market Stratification

Urban industries rely heavily on migrant workers for low-paying, labor-intensive jobs, including construction, manufacturing, domestic work, and sanitation. However, most migrants are excluded from stable, high-status employment because:

- Employers require local urban hukou for professional and government jobs.

- Migrants lack access to quality urban education and networks.

- They face discrimination due to stereotypes about rural workers.

This contributes to a dual labour market, reinforcing class divisions similar to Western theories of segmented labor markets.

C. Education Inequality and Intergenerational Impact

One of the most striking inequalities lies in education:

- Migrant children often cannot attend urban public schools.

- Many must return to their rural hometowns for high school due to hukou restrictions.

- University entrance exams (Gaokao) must typically be taken in one’s hukou locality.

Thus, students from rural areas face challenges competing with urban peers who benefit from better-funded schools and richer educational environments.

This perpetuates a cycle of intergenerational inequality, similar to Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital, where urban families pass on resources, networks, and cultural advantages that rural families lack.

3. The Rural–Urban Divide and Citizenship Inequality

The hukou system has effectively created two classes of citizenship in China:

Urban citizens

- Access to comprehensive welfare

- Better education

- Higher income opportunities

- Greater political representation in local governance

Rural citizens

- Limited welfare benefits

- Underfunded schools and healthcare facilities

- Higher dependence on migrant labour

- Social stigma associated with “ruralness”

This creates a hierarchical citizenship model, similar to sociologist T.H. Marshall’s distinction between civil, political, and social rights. While Chinese rural residents technically possess equal civil and political rights, their social rights are vastly unequal.

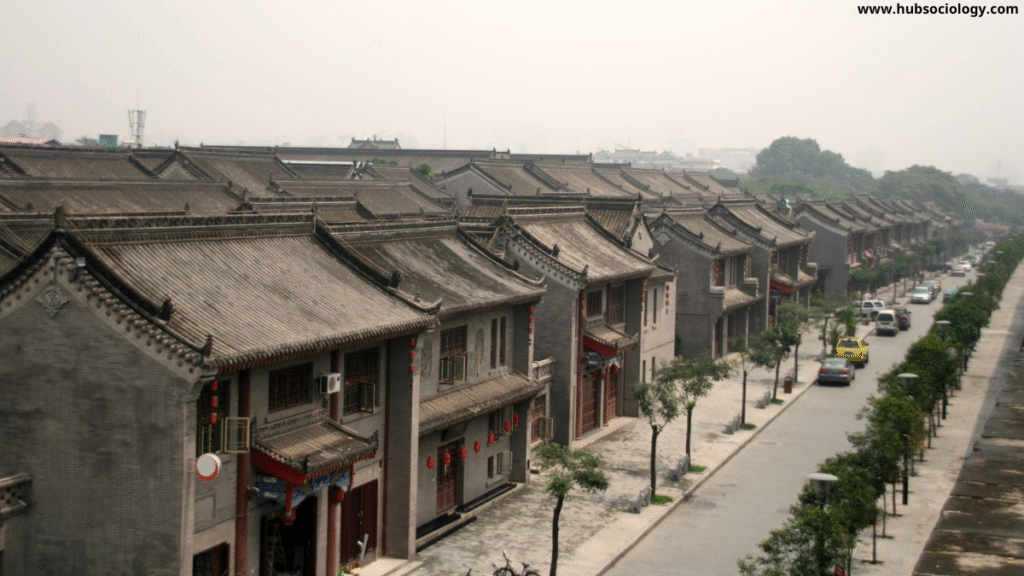

4. Urbanization and the Paradox of Economic Growth

China’s economic rise has been fueled by the massive movement of rural workers into cities—one of the largest human migrations in history. Today, over 290 million migrant workers contribute to urban economies. Yet, sociologically, this migration highlights a paradox:

- Cities depend on migrants for growth.

- But the hukou system prevents them from fully integrating.

Migrants often live in the urban shadows, occupying informal settlements, enduring unstable work conditions, and lacking welfare protection. They contribute to urban prosperity without enjoying its benefits—a clear example of structural exploitation.

The “left-behind” phenomenon

Because hukou restricts family migration, many migrant workers leave behind:

- Children (left-behind children)

- Elderly parents

- Spouses

This fragmentation of families produces emotional strain, reduced educational support for children, and rural poverty. Sociologically, it reflects how institutional rules shape family structures and social relationships.

5. Social Stigma, Identity, and Everyday Discrimination

Beyond material inequality, hukou also shapes social identity. Many urban residents perceive rural migrants as:

- Less “civilized”

- Poorly educated

- A threat to urban order

These stereotypes reinforce symbolic boundaries between urban and rural populations. Drawing on Erving Goffman’s theory of stigmatization, hukou becomes a “mark” that shapes how others perceive and interact with migrants. Even when migrants succeed economically, they may continue to face prejudice in housing, marriage markets, and social networks.

6. Hukou Reform: Progress and Limitations

China has attempted multiple reforms to modernize the hukou system and reduce inequalities:

Key reforms include:

- Removing agricultural vs. non-agricultural hukou distinctions (on paper)

- Allowing small and medium-sized cities to grant local hukou more easily

- Encouraging rural-to-urban hukou transfer in less-developed cities

- Implementing pilot programs for migrant children’s education access

However, major limitations persist:

1. Big cities remain highly restrictive

Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Guangzhou maintain strict points-based systems requiring:

- High income

- Advanced degrees

- Social insurance contributions

- Long-term residency

This creates an elite gateway to urban citizenship, reinforcing class privilege.

2. Rural land rights complicate reform

Rural hukou holders have collective land-use rights; giving up rural hukou may mean losing farmland—an important safety net.

3. Fiscal burdens

Local governments hesitate to grant urban hukou to migrants because they would need to expand expensive welfare services.

Thus, despite reforms, hukou continues to shape China’s social hierarchy.

7. Hukou and Class Formation in Contemporary China

Many sociologists argue that hukou is central to understanding China’s emerging class structure. It intersects with income, occupation, education, and capital to form distinct classes:

Urban middle class

Well-educated, stable employment, strong welfare support.

Urban working class

Usually local hukou holders engaged in manufacturing or service work but with social benefits.

Migrant working class

Low-paid, insecure jobs, limited rights—forming the “new precariat.”

Rural peasantry

Dependent on agriculture or seasonal migration.

Hukou thus institutionalizes class boundaries, making upward mobility harder for rural-born individuals.

8. Comparative Perspective: Hukou and Global Social Inequality

While hukou is unique, its sociological functions resemble global systems of inequality:

- Caste in India: Birth-based status, hereditary disadvantage.

- Race in the U.S.: Segregation in housing and education parallels urban-rural divisions.

- Immigration controls in Western countries: Migrants without citizenship face limited welfare access, similar to China’s rural migrants in cities.

These comparisons reveal hukou as part of larger global patterns where states regulate populations and control access to resources.

9. Emerging Social Movements and Public Attitudes

Although political activism in China is restricted, discussions around hukou inequalities have grown:

- Scholars critique its impact on equality of opportunity.

- Migrant workers express frustration through online platforms.

- Middle-class urban residents increasingly accept the idea of reform as labour shortages rise.

The sociological momentum behind hukou reform reflects shifting cultural attitudes and the growing recognition that sustained development requires integration rather than exclusion.

10. The Future of Hukou: Toward a More Inclusive Society?

Looking ahead, several trends are reshaping the future of the hukou system:

1. Economic need for labour mobility

As China’s population ages, cities need more migrant workers to maintain productivity.

2. Push for equal access to public services

Education and healthcare reforms are slowly opening urban institutions to migrant families.

3. Regional development strategies

Policies such as the Greater Bay Area promote cross-city mobility and may weaken hukou boundaries.

4. Technological governance

Digital identity systems may eventually replace traditional hukou documents, creating new possibilities—but also new concerns about surveillance and inequality.

While complete abolition remains unlikely soon, gradual reforms indicate movement toward a more equitable system.

Conclusion

China’s hukou system represents one of the most significant institutional contributors to social inequality in the modern world. Rooted in historical state objectives, it has evolved into a complex mechanism shaping citizenship status, resource allocation, labour markets, and identity. From limiting educational opportunities for migrant children to reinforcing class divisions in urban spaces, hukou continues to profoundly influence the lived experiences of hundreds of millions.

From a sociological perspective, the hukou system highlights how states create and maintain hierarchies through policy. It demonstrates the power of institutionalized boundaries to shape social mobility, stratification, and identity across generations. As China continues to urbanize and modernize, addressing hukou-based inequality will be crucial for building a more inclusive and cohesive society.

While reforms have made progress, the fundamental structure remains intact. True equality will require not just policy adjustments but a rethinking of the relationship between citizenship, welfare, and space in Chinese society. The future of hukou—and the millions whose lives are shaped by it—will depend on how China navigates the delicate balance between control, development, and social justice.

Do you like this this Article ? You Can follow as on :-

Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/hubsociology

WhatsApp Channel – https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029Vb6D8vGKWEKpJpu5QP0O

Gmail – hubsociology@gmail.com

15 FAQs on China’s Hukou System and Social Inequality

1. What is the hukou system in China?

The hukou system is a household registration system that classifies citizens as either rural or urban residents based on birthplace, determining access to education, healthcare, housing, and welfare.

2. How does the hukou system create social inequality?

It creates uneven access to public services. Urban hukou holders receive better education, healthcare, and welfare benefits, while rural hukou holders face institutional disadvantages even when living in cities.

3. Why was the hukou system originally introduced?

Introduced in 1958, the hukou system aimed to control internal migration, stabilize food supply, and support the planned economy by restricting rural-to-urban movement.

4. What is the difference between rural and urban hukou?

Urban hukou provides access to superior public services and welfare, while rural hukou holders often rely on agricultural land rights but lack equal access to urban benefits.

5. Who are “migrant workers” (liudong renkou) in China?

Migrant workers are rural hukou holders who move to cities for employment but cannot access full urban welfare rights because their hukou remains registered in their rural hometown.

6. How does hukou affect education opportunities?

Migrant children often cannot attend urban public schools or sit for high school and university entrance exams in big cities, limiting upward mobility.

7. Does hukou affect employment opportunities?

Yes. Many formal jobs, especially government and professional positions, require local urban hukou, forcing migrants into low-wage, unstable labor sectors.

8. How does hukou contribute to intergenerational inequality?

Because hukou status is inherited, children of rural hukou holders face disadvantages in education and welfare, perpetuating long-term social inequality.

9. What is the “left-behind children” problem?

Due to hukou restrictions, migrant workers often leave their children in rural areas. These children face emotional strain, poor education, and limited parental care.

10. Are big cities in China open to hukou transfer?

Major cities like Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen have strict points-based systems, making it difficult for ordinary workers to obtain local hukou, reinforcing elite privilege.

11. Has China attempted to reform the hukou system?

Yes, reforms include removing the rural/urban classification on paper, allowing hukou transfers in smaller cities, and expanding public service access for migrants. However, big cities remain restrictive.

12. Why is hukou reform difficult?

Reform is challenging due to financial burdens on local governments, preservation of rural land rights, and fear of overcrowding in major cities.

13. How does hukou affect access to healthcare?

Healthcare benefits are tied to hukou locality. Migrants in cities may not receive reimbursements or welfare support, pushing them toward low-quality or expensive services.

14. How does the hukou system influence class formation in China?

Hukou divides society into distinct classes—urban middle class, urban working class, migrant precariat, and rural peasantry—shaping income, occupation, and social mobility.

15. Will the hukou system be abolished in the future?

Complete abolition is unlikely soon, but gradual reforms are expected. China is opening smaller cities, improving migrant rights, and modernizing identity systems to reduce hukou-based inequality.