Introduction

Civil society has long been recognized as a crucial arena where citizens organize, express dissent, and negotiate power with the state. In Thailand, student protests have repeatedly emerged as one of the most dynamic expressions of civil society, particularly during moments of political crisis and democratic transition. From the 1970s to the contemporary youth-led movements of the 2020s, students have played a decisive role in shaping political consciousness, challenging authoritarianism, and redefining the boundaries of civic participation.

This article examines civil society and student protests in Thailand from a sociological perspective. It explores how student movements function as part of civil society, the structural and cultural conditions that enable protest, and the changing nature of political activism in a digitally connected society. By situating Thai student protests within broader sociological theories of civil society, social movements, and power, the article highlights their significance in Thailand’s ongoing struggle for democracy and social justice.

Understanding Civil Society in Sociological Terms

In sociology, civil society refers to the sphere of social life that exists between the state, the market, and the private household. It includes voluntary organizations, student unions, NGOs, professional associations, religious groups, and informal networks that allow citizens to collectively articulate interests and values.

Thinkers such as Alexis de Tocqueville emphasized civil society as a foundation of democracy, while Antonio Gramsci viewed it as a site of ideological struggle where dominant and counter-hegemonic ideas compete. In authoritarian or semi-democratic contexts like Thailand, civil society often becomes a contested space—simultaneously monitored by the state and used by citizens to resist domination.

Student movements occupy a special position within civil society. Universities provide physical spaces, intellectual resources, and social networks that facilitate political discussion and mobilization. Students often possess what sociologists call “relative autonomy”—they are educated, politically aware, and less constrained by family or economic responsibilities than other social groups.

Historical Background of Student Protests in Thailand

Student activism in Thailand is not a recent phenomenon. It has a long history closely tied to political upheavals and democratic aspirations.

The 1973 Student Uprising

The modern Thai student movement gained national prominence in October 1973, when students led mass protests against military dictatorship. The uprising resulted in the temporary collapse of authoritarian rule and demonstrated the power of organized civil society. Universities became centers of political debate, and students were widely seen as moral leaders of the nation.

The 1976 Thammasat Tragedy

The optimism of the early 1970s was brutally shattered in October 1976, when state forces violently suppressed student protesters at Thammasat University. This event marked a turning point, showing the limits of civil society under repressive conditions. Sociologically, it illustrates how the state can use violence to dismantle civic spaces when protest challenges entrenched power structures.

Post-1990s Democratization and New Movements

Following the 1992 “Black May” protests and the 1997 Constitution, civil society expanded significantly in Thailand. Student activism became less revolutionary and more issue-based, focusing on human rights, environmental concerns, and constitutional reform. However, military coups in 2006 and 2014 once again constrained civic freedoms, reshaping the nature of student protests.

Civil Society and the 2020–2021 Student-Led Protests

The student-led protests that began in 2020 marked a new phase in Thai civil society. These movements were notable not only for their scale but also for their ideological clarity and organizational style.

Key Features of the Movement

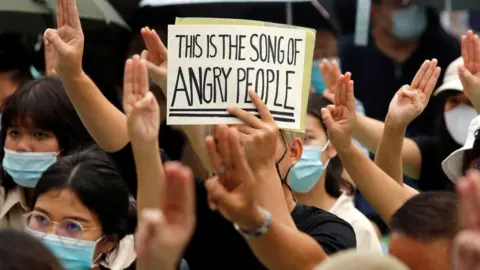

Unlike earlier protests, the 2020 student movement openly addressed previously taboo topics, including military dominance and the role of the monarchy in politics. From a sociological standpoint, this represents a normative shift—a transformation in what society considers discussable and legitimate in the public sphere.

The movement was largely decentralized, leader-light, and digitally organized. Social media platforms replaced traditional student unions as tools of mobilization. This reflects Manuel Castells’ theory of networked social movements, where power is exercised through communication networks rather than hierarchical organizations.

Youth Identity and Political Consciousness

Sociologically, these protests were also expressions of generational identity. Young people facing economic precarity, limited job opportunities, and restricted political freedoms used protest as a means of asserting citizenship. Their activism reflected a clash between traditional authority and emerging democratic values, especially around freedom of expression and equality.

Universities as Spaces of Civil Society

Universities in Thailand function as critical sites of civil society. They provide institutional legitimacy, symbolic power, and physical space for protest. However, they are also subject to state surveillance and regulation.

From a conflict theory perspective, universities can be seen as arenas where dominant ideologies are reproduced but also contested. Student protests disrupt the “hidden curriculum” that promotes obedience and nationalism, replacing it with critical thinking and dissent.

Faculty members, alumni, and academic networks often act as intermediaries between students and broader civil society, lending credibility to movements and expanding their reach beyond campus boundaries.

State Response and the Shrinking Civic Space

A key sociological dimension of student protests in Thailand is the state’s response. Legal repression, surveillance, and the use of emergency laws have significantly constrained civil society.

The use of lèse-majesté laws and public assembly restrictions illustrates what sociologists describe as authoritarian resilience—the ability of non-democratic regimes to adapt and survive by controlling civic space without completely eliminating it. This creates a paradoxical situation where civil society exists but operates under constant threat.

Despite repression, student activism persists, suggesting that civil society in Thailand is not merely institutional but also cultural and symbolic. Protest has become a form of political socialization for a new generation.

Role of NGOs and Wider Civil Society

Student movements in Thailand do not operate in isolation. NGOs, human rights organizations, lawyers’ groups, and online activist communities form a broader civil society ecosystem. These actors provide legal aid, media visibility, and international connections.

From a sociological lens, this collaboration reflects resource mobilization theory, which emphasizes that successful social movements depend not only on grievances but also on access to organizational and material resources.

However, tensions sometimes arise between students and established NGOs, particularly over leadership, strategy, and negotiation with the state. These tensions reveal class, generational, and ideological differences within civil society itself.

Gender, Culture, and Protest

Another important sociological aspect of Thai student protests is gender participation. Young women and LGBTQ+ activists have been highly visible in leadership roles, challenging patriarchal norms embedded in Thai society.

Cultural symbols, satire, and performance have played a central role in protests, making them accessible and emotionally resonant. This aligns with cultural sociology, which emphasizes meaning, symbols, and identity in collective action rather than viewing protest purely as a rational response to political conditions.

Challenges Facing Student-Led Civil Society

Despite its vitality, student activism in Thailand faces significant challenges. Repression leads to protest fatigue, fear, and fragmentation. Economic pressures force many activists to prioritize survival over sustained engagement.

There is also the risk of depoliticization, as movements lose momentum without institutional pathways for reform. Sociologically, this raises questions about the sustainability of civil society under authoritarian conditions and the limits of protest without structural change.

Conclusion

Civil society and student protests in Thailand represent one of the most significant forces shaping the country’s political and social landscape. From historical uprisings to contemporary digital movements, students have consistently acted as catalysts for democratic debate and civic awareness.

A sociological analysis reveals that these protests are not spontaneous outbursts but structured responses shaped by institutions, culture, generational identity, and power relations. Even in the face of repression, student-led civil society continues to redefine political participation in Thailand.

Ultimately, the future of Thai democracy is closely linked to the resilience of its civil society and the ability of students to transform protest into lasting social change. Their struggle highlights a universal sociological truth: where civic space is constrained, resistance often finds new and creative forms.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): Student Protests in Thailand

1. What are student protests in Thailand?

Student Protests in Thailand refer to organized political movements led by students who demand democratic reforms, civil liberties, and greater accountability from the state.

2. Why are student protests important in Thailand’s civil society?

Student Protests in Thailand are important because they strengthen civil society by promoting political participation, freedom of expression, and democratic awareness.

3. When did student protests first emerge in Thailand?

Student Protests in Thailand became prominent in the early 1970s, especially during the 1973 uprising against military dictatorship.

4. How do student protests reflect sociological conflict?

From a sociological perspective, Student Protests in Thailand represent conflict between state power and youth demands for equality, rights, and democratic governance.

5. What role do universities play in student protests in Thailand?

Universities act as key spaces for Student Protests in Thailand, providing organizational networks, ideological debate, and symbolic legitimacy.

6. How are student protests connected to civil society in Thailand?

Student Protests in Thailand function as an active component of civil society by mobilizing citizens and challenging authoritarian control.

7. What issues do student protesters in Thailand usually raise?

Common issues in Student Protests in Thailand include constitutional reform, freedom of speech, military influence in politics, and social justice.

8. How has social media influenced student protests in Thailand?

Social media has transformed Student Protests in Thailand by enabling decentralized leadership, rapid mobilization, and global visibility.

9. What challenges do student protesters face in Thailand?

Student Protests in Thailand face challenges such as legal repression, surveillance, arrests, and restrictions on public assembly.

10. How does the Thai state respond to student protests?

The state often responds to Student Protests in Thailand through legal action, policing, and control over civic spaces.

11. Are student protests in Thailand peaceful?

Most Student Protests in Thailand are peaceful and rely on symbolic resistance, cultural expression, and non-violent demonstrations.

12. What sociological theories explain student protests in Thailand?

Theories such as conflict theory, civil society theory, and social movement theory help explain Student Protests in Thailand.

13. How do student protests influence democracy in Thailand?

Student Protests in Thailand contribute to democratic development by questioning authority and expanding political debate.

14. What role do youth identities play in student protests?

Youth identity is central to Student Protests in Thailand, as students challenge traditional hierarchies and demand generational justice.

15. What is the future of student protests in Thailand?

The future of Student Protests in Thailand depends on the resilience of civil society and the possibility of political reforms.