Introduction on Max Weber on Power

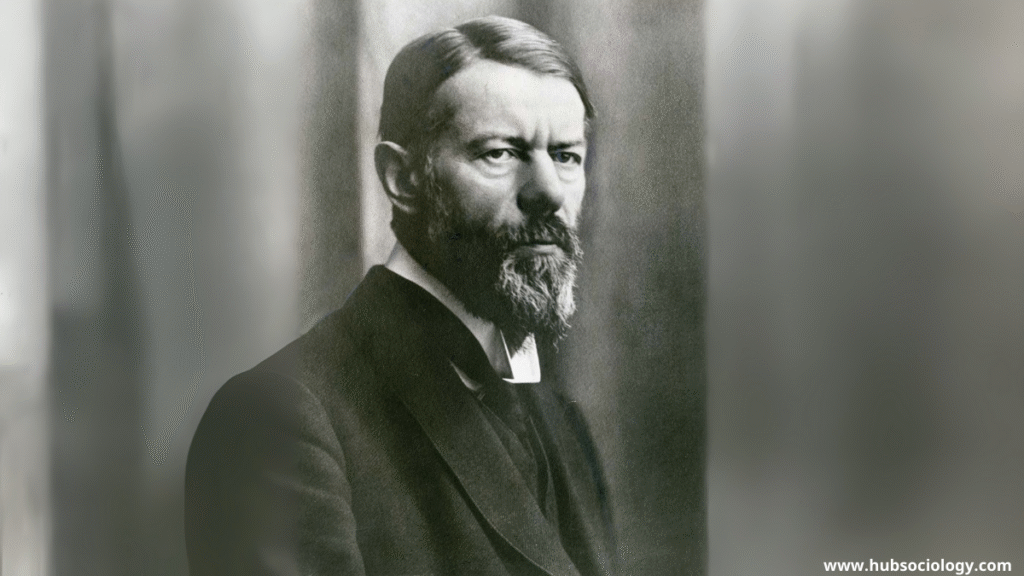

Power has always been central to human society, shaping the organization of communities, states, and global structures. Among the classical sociologists, Max Weber (1864–1920) stands as one of the most influential thinkers in understanding power and authority. His analysis, rooted in sociology and political theory, offers timeless insights into how power functions, how it is legitimized, and how it shapes political institutions. In today’s world—marked by populism, authoritarian resurgence, global inequality, and crises of democracy—Weber’s conceptualization of power provides valuable tools to interpret and critique modern politics.

This article explores Weber’s definition of power, his distinction between power (Macht) and authority (Herrschaft), his typology of legitimate domination, and the lessons that contemporary politics can draw from his ideas. Through a sociological lens, it shows how Weber’s framework helps us understand political dynamics, the crisis of legitimacy in governments, the role of bureaucracy, and the challenges of globalization and digital politics.

Table of Contents on Max Weber on Power

Max Weber’s Concept of Power

Weber defined power (Macht) in his work Economy and Society as:

“The probability that one actor within a social relationship will be in a position to carry out his own will despite resistance, regardless of the basis on which this probability rests.”

This definition emphasizes two sociological dimensions:

- Relational Nature of Power – Power exists in social interactions; it is never isolated but embedded in relationships between individuals and groups.

- Resistance and Compliance – Power is meaningful only when there is resistance to overcome, making it different from voluntary cooperation.

Unlike Karl Marx, who tied power directly to economic structures and class domination, Weber approached power more broadly. He recognized multiple sources of power—economic, political, social, and cultural. For Weber, power is not only about resources but also about legitimacy and recognition.

Power versus Authority

A key contribution of Weber was distinguishing power from authority (legitimate power). While power can be coercive, authority implies that those subjected to it accept it as rightful. Weber categorized authority into three types:

- Traditional Authority – Legitimacy based on customs, traditions, and established practices. Examples include monarchies, tribal chiefs, and hereditary rule.

- Charismatic Authority – Legitimacy derived from the personal qualities of a leader, often seen as extraordinary or divinely inspired. Leaders like Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., or even modern populist figures exhibit this.

- Rational-Legal Authority – Legitimacy based on formal rules, laws, and bureaucratic procedures. Modern states and democratic institutions primarily rely on this form.

This typology remains central to sociology and political science, offering a lens to understand not only historical governance systems but also the hybrid political realities of today.

Weber and Bureaucracy

Weber also emphasized the role of bureaucracy in modern states, describing it as the most efficient and rational form of organization. Bureaucracy, characterized by hierarchy, specialization, and impersonal rules, enables rational-legal authority to function.

Yet, Weber warned of the “iron cage” of bureaucracy, where excessive rationalization and control could stifle freedom and creativity. In today’s politics, this tension is evident—citizens expect efficiency and fairness in public institutions but also criticize red tape, corruption, and lack of responsiveness.

Lessons from Weber for Today’s Politics

1. Legitimacy as the Foundation of Political Power

Weber’s greatest lesson for contemporary politics is the importance of legitimacy. In many democracies, there is a growing crisis of legitimacy, where citizens feel disconnected from political elites. Low voter turnout, mistrust in government institutions, and the rise of populist movements reflect this.

Weber helps us see that power without legitimacy is fragile. A government may enforce laws through coercion, but long-term stability requires the acceptance of authority as rightful. For instance, the 21st century has seen authoritarian regimes use propaganda and nationalism to legitimize themselves, while democracies rely on legal-rational procedures such as elections and constitutional checks. Understanding this helps us analyze why some governments endure despite repression and why others collapse despite economic strength.

2. The Return of Charismatic Leadership

Weber’s concept of charisma resonates deeply in the 21st century. From Donald Trump in the U.S. to Narendra Modi in India, from Volodymyr Zelenskyy in Ukraine to Jair Bolsonaro in Brazil, politics has been reshaped by charismatic figures who command mass loyalty beyond institutional structures.

Social media amplifies charisma, enabling leaders to bypass traditional institutions and directly connect with the public. Weber’s insight shows both the strength and danger of charisma—it can inspire revolutionary change but also destabilize rational-legal systems. The challenge for modern democracies is balancing charismatic mobilization with institutional safeguards.

3. Traditional Authority in Modern Politics

Although modern states are largely rational-legal, elements of traditional authority persist. In South Asia, dynastic politics dominates parties in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh. In the Middle East, monarchies retain legitimacy through tradition and religion. Even in Western democracies, rituals, ceremonies, and traditions (such as the British monarchy or U.S. presidential inaugurations) carry symbolic authority.

Weber’s framework encourages us to see that political systems are rarely pure; they often combine traditional, charismatic, and rational-legal elements.

4. Bureaucracy and the “Iron Cage” in the Digital Age

Weber’s warnings about bureaucratic domination find new relevance in the digital era. Modern bureaucracies are increasingly influenced by data-driven governance, surveillance technologies, and artificial intelligence. Citizens face not only paperwork but also algorithmic decisions that affect welfare benefits, policing, and even electoral campaigns.

This is a new “iron cage,” where rationalization takes the form of digital control. The sociological challenge today is ensuring that bureaucracy remains accountable and humane rather than oppressive and dehumanizing.

5. Power Beyond the Nation-State

Weber wrote in an era when the nation-state was the dominant political form. Today, globalization has dispersed power beyond national governments—multinational corporations, international organizations, and digital platforms (like Google, Meta, and X) wield enormous influence.

Weber’s broad definition of power reminds us that politics is not limited to parliaments or presidents. Global institutions like the United Nations or the International Monetary Fund exercise rational-legal authority, while corporations use both economic dominance and charismatic branding. This calls for a sociological rethinking of political legitimacy at a transnational scale.

6. Conflict and Resistance in Power Relations

Weber highlighted that power exists where there is resistance. In contemporary society, social movements—from climate justice to Black Lives Matter, from farmer protests in India to pro-democracy movements in Hong Kong—illustrate this principle. These movements challenge state power and demand legitimacy by appealing to both rational-legal frameworks (rights, constitutions) and charismatic leadership.

Weber helps us understand that resistance is not a breakdown of politics but an integral part of power relations. Modern politics cannot be analyzed without considering how marginalized groups contest power.

7. The Ethics of Responsibility in Leadership

Weber, in his famous lecture Politics as a Vocation, distinguished between the ethic of conviction (acting on moral principles regardless of consequences) and the ethic of responsibility (considering the outcomes of actions).

Today’s political leaders face dilemmas where these ethics collide—such as balancing security with human rights, economic growth with climate change, or free speech with digital misinformation. Weber’s call for a politics of responsibility resonates strongly, reminding leaders that ethical responsibility, not just charisma or ideology, must guide political decision-making.

Contemporary Illustrations of Weber’s Relevance

- Populism – The rise of populist leaders shows how charisma can disrupt rational-legal authority, creating both mobilization and polarization.

- Crisis of Democracy – In countries like the U.S. or parts of Europe, declining trust in institutions reflects Weber’s concern with legitimacy.

- Authoritarian Stability – Regimes like China’s combine rational-legal authority (bureaucracy), charisma (Xi Jinping), and tradition (Confucian heritage) to maintain power.

- Digital Governance – The surveillance state in China, algorithmic policing in the U.S., and data-driven elections globally illustrate the new “iron cage” of bureaucracy.

- Global Power Shifts – Multinational corporations and digital giants wield power that Weber’s framework can still analyze, even if he did not foresee their rise.

Critical Evaluation of Weber’s Perspective

While Weber’s ideas remain deeply influential, they also have limitations:

- Eurocentric Bias – His typology of authority was derived from Western history, though scholars have applied it globally.

- Static Categories – Modern politics often mixes forms of authority in ways that Weber’s neat classification struggles to capture.

- Neglect of Economic Power – Compared to Marx, Weber’s analysis sometimes underplays structural economic domination.

- Optimism about Rational-Legal Authority – Weber saw bureaucracy as rational, but in practice it often perpetuates inequality and exclusion.

Nevertheless, these limitations do not diminish the relevance of Weber’s framework; rather, they invite sociologists to adapt his ideas to contemporary realities.

Conclusion on Max Weber on Power

Max Weber’s insights on power and authority remain central to the sociological study of politics. His distinction between power and legitimate authority, his typology of domination, and his warnings about bureaucracy provide essential tools for analyzing today’s political crises.

In a world where democracies are under strain, authoritarian regimes are resurging, and digital technologies reshape governance, Weber’s work teaches us that legitimacy, responsibility, and institutional balance are the foundations of political order.

For today’s politics, the lessons are clear: power must be understood not just as domination but as legitimacy; charismatic leadership must be balanced with rational institutions; bureaucracies must serve people rather than trap them; and leaders must act with responsibility.

Weber’s vision was not merely academic—it was a call to critically examine power in all its forms. In this sense, his sociology continues to illuminate the challenges of our time, reminding us that politics is ultimately about shaping the destiny of human communities.

Do you like this this Article ? You Can follow as on :-

Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/hubsociology

Whatsapp Channel – https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029Vb6D8vGKWEKpJpu5QP0O

Gmail – hubsociology@gmail.com

10 FAQs on Max Weber on Power

Q1. What does Max Weber mean by power?

Max Weber on Power defines it as the probability that an individual or group can impose their will within a social relationship, even against resistance. It highlights power as relational and embedded in society.

Q2. How does Max Weber differentiate power from authority?

According to Max Weber on Power, authority is a legitimate form of power accepted by those governed, whereas power itself can be coercive or based on force without legitimacy.

Q3. What are the types of authority in Max Weber’s theory of power?

Max Weber on Power identifies three forms of authority: traditional authority (based on customs), charismatic authority (based on personal qualities of a leader), and rational-legal authority (based on rules and laws).

Q4. Why is Max Weber’s concept of power relevant today?

Max Weber on Power helps us understand modern politics, especially issues of legitimacy, the rise of charismatic leaders, the role of bureaucracy, and the global distribution of power.

Q5. What role does legitimacy play in Max Weber’s view of power?

For Max Weber on Power, legitimacy is the foundation of stable authority. Governments and leaders can maintain authority only if citizens recognize their power as rightful.

Q6. How does bureaucracy relate to Max Weber on Power?

In Max Weber on Power, bureaucracy is described as the most rational form of administration. It supports rational-legal authority but can also create an “iron cage” that limits individual freedom.

Q7. What is the significance of charismatic authority in Max Weber’s theory of power?

Max Weber on Power shows that charismatic authority plays a transformative role in politics. Charismatic leaders inspire loyalty but may destabilize institutions if unchecked.

Q8. How does Max Weber on Power compare to Karl Marx’s view of power?

While Marx linked power mainly to economic class domination, Max Weber on Power takes a broader view, recognizing that power can arise from social status, political influence, culture, and legitimacy.

Q9. How can Max Weber on Power explain today’s global politics?

Max Weber on Power is useful for analyzing modern trends such as populism, authoritarianism, digital surveillance, and the influence of multinational corporations beyond the state.

Q10. What ethical lessons can leaders learn from Max Weber on Power?

Max Weber on Power stresses the importance of the “ethic of responsibility,” urging leaders to balance moral principles with practical consequences in political decision-making.