Introduction on Sociology of Caste in South Asia

The sociology of caste is one of the most enduring and complex social structures in South Asia, shaping the socio-political and economic lives of millions of people across India, Nepal, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka. Rooted in ancient Hindu scriptures but extending beyond religious boundaries, caste operates as a rigid hierarchical system that dictates social stratification, occupation, marriage, and access to resources. From a sociological perspective, caste is not merely a religious or cultural phenomenon but a deeply institutionalized system of inequality, power, and identity. This article examines the sociology of caste in South Asia by exploring its historical foundations, theoretical interpretations, functional and conflict perspectives, and its contemporary transformations in a rapidly modernizing region.

Table of Contents

Historical Foundations of Caste

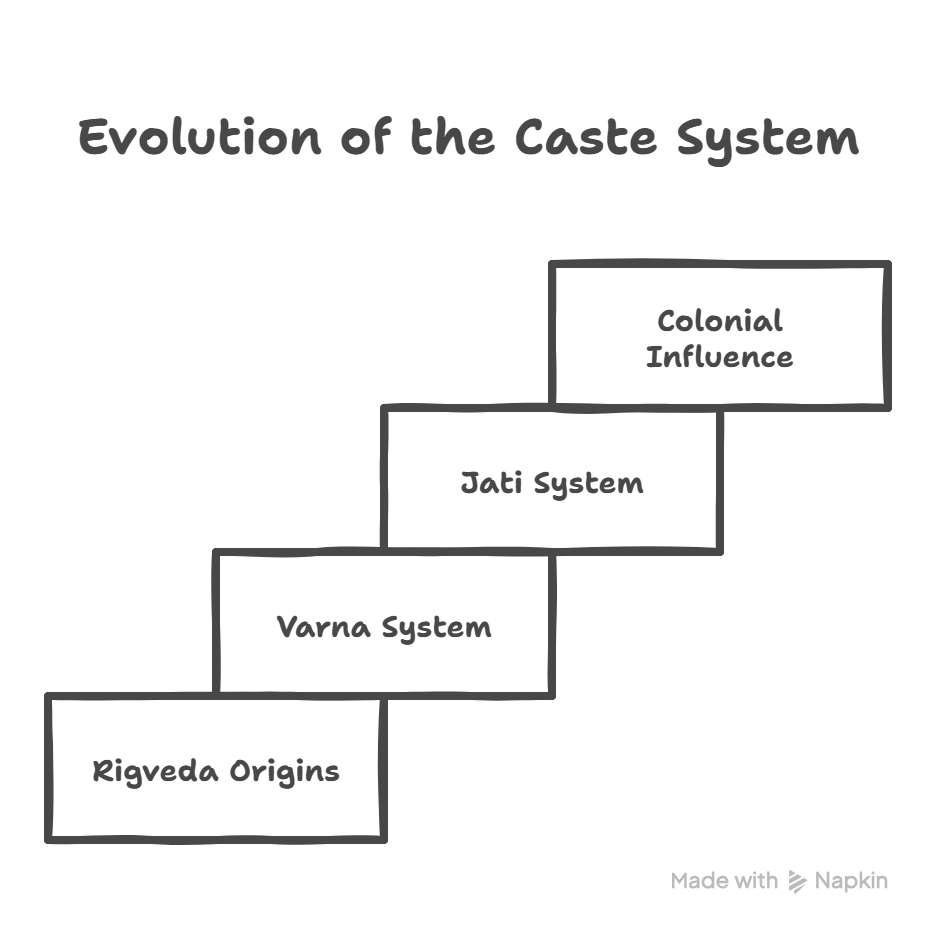

The origins of the caste system can be traced back to the ancient Hindu text, the Rigveda (1500 BCE), which introduces the varna system—a four-fold classification of society into Brahmins (priests and scholars), Kshatriyas (warriors and rulers), Vaishyas (merchants and farmers), and Shudras (servants and laborers). Outside this hierarchy were the Dalits (formerly “untouchables”), who were relegated to the most degrading occupations.

Over time, the varna system evolved into the jati system, which is more localized and occupation-based, with thousands of sub-castes governing social interactions. Colonial rule further rigidified caste through census classifications and administrative policies, making caste a central category in governance and identity politics.

Theoretical Perspectives on Caste

Sociologists have approached caste from various theoretical frameworks:

1. Structural-Functionalist Perspective

Functionalists like Emile Durkheim and G.S. Ghurye viewed caste as a system that maintained social order by assigning fixed roles to individuals, ensuring division of labor and social cohesion. According to this view:

- Caste provided economic stability by hereditary occupations.

- It reinforced social solidarity through endogamy (marriage within caste).

- Ritual purity and pollution norms maintained cultural continuity.

However, critics argue that this perspective ignores caste-based oppression and exploitation, treating an unequal system as “functional.”

2. Conflict Perspective

Marxist sociologists, including D.D. Kosambi and Gail Omvedt, interpret caste as a tool of economic exploitation. They argue:

- The upper castes (Brahmins, Kshatriyas) historically controlled land and resources, while lower castes provided cheap labor.

- Caste intersects with class, where Dalits and Shudras form the proletariat, while dominant castes act as the bourgeoisie.

- Caste perpetuates itself through ideological hegemony (via religion and culture) to justify inequality.

3. Weberian Perspective

Max Weber saw caste as a closed status group where social honor (prestige) was monopolized by higher castes. Unlike class (economic position), caste was about ritual status and social exclusion. Weber argued that caste hindered capitalist development by restricting occupational mobility.

4. Ambedkarite and Subaltern Perspectives

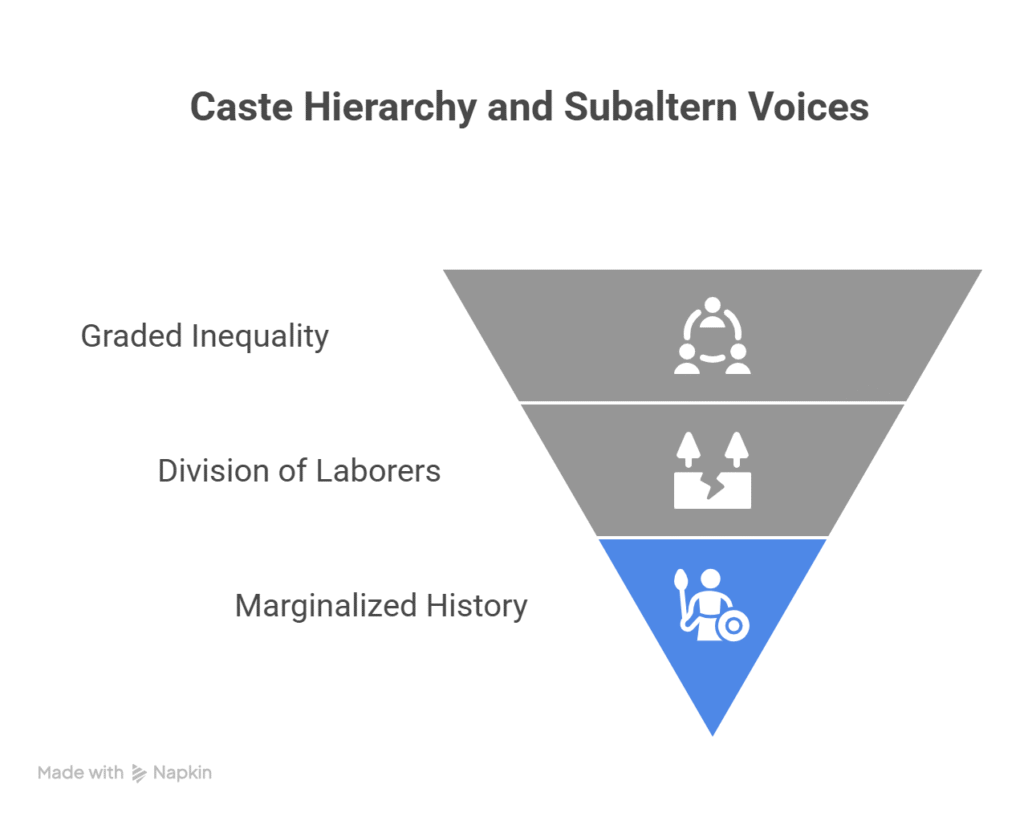

B.R. Ambedkar, a Dalit scholar and architect of India’s constitution, viewed caste as a system of graded inequality, where each caste oppresses the one below it. He emphasized that caste was not just division of labor but division of laborers, enforced through violence and social boycott. Subaltern studies scholars like Gyanendra Pandey and Dipesh Chakrabarty highlight how caste operates at the margins of history, often suppressed in dominant narratives.

Caste in Contemporary South Asia

Despite constitutional bans on caste discrimination (e.g., India’s Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Prevention of Atrocities Act), caste remains deeply entrenched in South Asian societies. Its manifestations today include:

1. Political Mobilization

Caste has become a key factor in electoral politics. Parties like the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) in India represent Dalit interests, while dominant castes (e.g., Jats, Yadavs) form powerful voting blocs. Reservation policies (affirmative action) for lower castes in education and jobs have both empowered marginalized groups and sparked upper-caste backlash.

2. Economic Inequality

Caste continues to influence economic opportunities:

- Dalits are disproportionately engaged in manual scavenging, sanitation work, and landless labor.

- Dominant castes control most businesses, political offices, and educational institutions.

- Globalization has created new caste dynamics, with urban Dalits entering corporate sectors but facing subtle discrimination.

3. Social and Cultural Persistence

- Endogamy: Inter-caste marriages remain rare (less than 5% in India), upheld by family honor and social stigma.

- Violence: Honor killings, caste-based atrocities, and discrimination persist, especially in rural areas.

- Modern Forms of Untouchability: Segregation in housing, temples, and public spaces continues informally.

4. Transnational Caste Networks

The South Asian diaspora (in the U.S., UK, Gulf) reproduces caste hierarchies abroad. Cases of caste discrimination in Silicon Valley tech firms and UK workplaces highlight its global persistence.

Challenges and Transformations on Sociology of Caste in South Asia

While caste remains oppressive, social changes are occurring:

- Education and Urbanization: Younger generations are increasingly rejecting rigid caste identities.

- Inter-caste Solidarities: Movements like Dalit-Bahujan activism challenge Brahminical hegemony.

- Legal Reforms: Stronger anti-discrimination laws and digital activism (e.g., #DalitLivesMatter) are pushing for accountability.

However, caste adapts rather than disappears—modern capitalism and neoliberalism often reinforce caste privilege in new ways (e.g., corporate caste networks).

Conclusion on Sociology of Caste in South Asia

The sociology of caste in South Asia reveals a system that is both ancient and dynamically evolving. While functionalists see caste as a stabilizing force, conflict theorists expose its exploitative nature. Contemporary South Asia witnesses both the resilience of caste hierarchies and emerging resistance movements.

The future of caste depends on how effectively legal, economic, and cultural interventions can dismantle its oppressive structures while empowering marginalized communities. As South Asia modernizes, the interplay between caste, class, and globalization will continue to shape its social fabric.

Do you like this this Article ? You Can follow as on :-

Facebook – https://www.facebook.com/hubsociology

Whatsapp Channel – https://whatsapp.com/channel/0029Vb6D8vGKWEKpJpu5QP0O

Gmail – hubsociology@gmail.com

Topic Related Questions on Sociology of Caste in South Asia

5-Mark Questions on Sociology of Caste in South Asia (Short Answer Type)

- Define caste and distinguish it from class.

- What is the Varna system? Briefly explain its four divisions.

- How did colonialism impact the caste system in South Asia?

- What is meant by ‘Sanskritization’ in the context of caste mobility?

- Explain the concept of ‘Dalit’ and its significance in caste studies.

- What role does endogamy play in maintaining the caste system?

- Name two major social reformers who fought against caste discrimination in India.

- How does caste influence occupational roles in traditional South Asian society?

- What is the difference between jati and varna?

- How does the caste system manifest in urban areas today?

10-Mark Questions on Sociology of Caste in South Asia (Descriptive Answer Type)

- Discuss the structural-functionalist perspective on caste. How does it explain caste as a stabilizing force?

- Analyze the Marxist (conflict theory) view of caste as a system of exploitation.

- Explain the concept of ‘reservation’ in India. How has it impacted caste-based inequalities?

- Discuss B.R. Ambedkar’s critique of the caste system and his vision for an egalitarian society.

- How does caste intersect with gender in South Asia? Provide examples.

- What is the role of caste in electoral politics in contemporary India?

- Examine the persistence of untouchability in modern South Asia despite legal prohibitions.

- How has globalization affected caste dynamics in South Asia?

- Discuss the impact of education and urbanization on caste identities.

- Compare and contrast the caste system in India with similar social hierarchies in Nepal or Pakistan.

15-Mark Questions on Sociology of Caste in South Asia (Essay/Long Answer Type)

- Critically examine the role of caste in shaping social, economic, and political structures in South Asia.

- “Caste is not just a relic of the past but a living reality in modern South Asia.” Discuss with examples.

- Evaluate the effectiveness of affirmative action (reservation policies) in addressing caste-based discrimination in India.

- How does the caste system perpetuate inequality? Discuss with reference to theories of social stratification.

- Analyze the changing nature of caste in the context of globalization, urbanization, and digital activism.

- Compare the functionalist and conflict perspectives on the caste system. Which one better explains its persistence?

- Discuss the role of religion and ideology in legitimizing the caste system in South Asia.

- How have social movements (e.g., Dalit movements, anti-caste activism) challenged the caste hierarchy?

- “Caste and class are intertwined but not identical.” Elaborate on this statement with sociological insights.

- Examine the impact of British colonial policies on the institutionalization of caste in India.

1 thought on “The Sociology of Caste in South Asia: A Structural and Functional Analysis”